When I lived in Windsor there used to be a set of The Secret Doctrine. It is ofcourse a great all-time classic... RS

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia/Blogger Ref http://www.p2pfoundation.net/Multi-Dimensional_Science

For the Morgana Lefay album, see The Secret Doctrine (album).

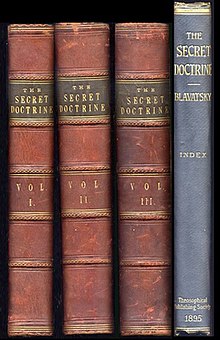

First edition

| |

| Author | Helena Blavatsky |

|---|---|

| Published | 1888 |

| Part of a series on |

| Theosophy |

|---|

|

| Theosophy |

Blavatsky claimed that its contents had been revealed to her by 'mahatmas' who had retained knowledge of humanity's spiritual history, knowledge that it was now possible, in part, to reveal.[not verified in body]

Contents

[hide]- 1 Volume one (Cosmogenesis)

- 2 Volume two (Anthropogenesis)

- 3 Volumes three and four

- 4 Three fundamental propositions

- 5 Theories on human evolution and race

- 6 Study of the Secret Doctrine

- 7 Writings about "The Secret Doctrine"

- 8 Critical reception

- 9 See also

- 10 Notes

- 11 References

- 12 Bibliography

- 13 External links

Volume one (Cosmogenesis)[edit]

The first part of the book explains the origin and evolution of the universe itself, in terms derived from the Hindu concept of cyclical development. The world and everything in it is said to alternate between periods of activity (manvantaras) and periods of passivity (pralayas). Each manvantara lasts many millions of years and consists of a number of Yugas, in accordance with Hindu cosmology.Blavatsky attempted to demonstrate that the discoveries of "materialist" science had been anticipated in the writings of ancient sages and that materialism would be proven wrong.

Cosmic evolution: Items of cosmogony[edit]

In this recapitulation of The Secret Doctrine, Blavatsky gave a summary of the central points of her system of cosmogony.[1] These central points are as follows:- The first item reiterates Blavatsky's position that The Secret Doctrine represents the "accumulated Wisdom of the Ages", a system of thought that "is the uninterrupted record covering thousands of generations of Seers whose respective experiences were made to test and to verify the traditions passed orally by one early race to another, of the teachings of higher and exalted beings, who watched over the childhood of Humanity."

- The second item reiterates the first fundamental proposition (see above), calling the one principle "the fundamental law in that system [of cosmogony]". Here Blavatsky says of this principle that it is "the One homogeneous divine Substance-Principle, the one radical cause. … It is called "Substance-Principle," for it becomes "substance" on the plane of the manifested Universe, an illusion, while it remains a "principle" in the beginningless and endless abstract, visible and invisible Space. It is the omnipresent Reality: impersonal, because it contains all and everything. Its impersonality is the fundamental conception of the System. It is latent in every atom in the Universe, and is the Universe itself."

- The third item reiterates the second fundamental proposition (see above), impressing once again that "The Universe is the periodical manifestation of this unknown Absolute Essence.", while also touching upon the complex Sanskrit ideas of Parabrahmam and Mulaprakriti. This item presents the idea that the One unconditioned and absolute principle is covered over by its veil, Mulaprakriti, that the spiritual essence is forever covered by the material essence.

- The fourth item is the common eastern idea of Maya. Blavatsky states that the entire universe is called illusion because everything in it is temporary, i.e. has a beginning and an end, and is therefore unreal in comparison to the eternal changelessness of the One Principle.

- The fifth item reiterates the third fundamental proposition (see above), stating that everything in the universe is conscious, in its own way and on its own plane of perception. Because of this, the Occult Philosophy states that there are no unconscious or blind laws of Nature, that all is governed by consciousness and consciousnesses.

- The sixth item gives a core idea of theosophical philosophy, that "as above, so below". This is known as the "law of correspondences", its basic premise being that everything in the universe is worked and manifested from within outwards, or from the higher to the lower, and that thus the lower, the microcosm, is the copy of the higher, the macrocosm. Just as a human being experiences every action as preceded by an internal impulse of thought, emotion or will, so too the manifested universe is preceded by impulses from divine thought, feeling and will. This item gives rise to the notion of an "almost endless series of hierarchies of sentient beings", which itself becomes a central idea of many theosophists. The law of correspondences also becomes central to the methodology of many theosophists, as they look for analogous correspondence between various aspects of reality, for instance: the correspondence between the seasons of Earth and the process of a single human life, through birth, growth, adulthood and then decline and death.

Volume two (Anthropogenesis)[edit]

The second half of the book describes the origins of humanity through an account of "Root Races" said to date back millions of years. The first root race was, according to her, "ethereal"; the second root had more physical bodies and lived in Hyperborea. The third root race, the first to be truly human, is said to have existed on the lost continent of Lemuria and the fourth root race is said to have developed in Atlantis.According to Blavatsky, the fifth root race is approximately one million years old, overlapping the fourth root race and the very first beginnings of the fifth root race were approximately in the middle of the fourth root race.[citation needed]

"The real line of evolution differs from the Darwinian, and the two systems are irreconcilable," according to Blavatsky, "except when the latter is divorced from the dogma of 'Natural Selection'." She explained that, "by 'Man' the divine Monad is meant, and not the thinking Entity, much less his physical body." "Occultism rejects the idea that Nature developed man from the ape, or even from an ancestor common to both, but traces, on the contrary, some of the most anthropoid species to the Third Race man." In other words, "the 'ancestor' of the present anthropoid animal, the ape, is the direct production of the yet mindless Man, who desecrated his human dignity by putting himself physically on the level of an animal."[2]

Volumes three and four[edit]

Blavatsky wanted to publish a third and fourth volume of The Secret Doctrine. After Blavatsky's death, a controversial third volume of The Secret Doctrine was published by Annie Besant.[citation needed]Three fundamental propositions[edit]

Blavatsky explained the essential component ideas of her cosmogony in her magnum opus, The Secret Doctrine. She began with three fundamental propositions, of which she said:Before the reader proceeds … it is absolutely necessary that he should be made acquainted with the few fundamental conceptions which underlie and pervade the entire system of thought to which his attention is invited. These basic ideas are few in number, and on their clear apprehension depends the understanding of all that follows…[3]The first proposition is that there is one underlying, unconditioned, indivisible Truth, variously called "the Absolute", "the Unknown Root", "the One Reality", etc. It is causeless and timeless, and therefore unknowable and non-describable: "It is 'Be-ness' rather than Being".[a] However, transient states of matter and consciousness are manifested in IT, in an unfolding gradation from the subtlest to the densest, the final of which is physical plane.[4] According to this view, manifest existence is a "change of condition"[b] and therefore neither the result of creation nor a random event.

Everything in the universe is informed by the potentialities present in the "Unknown Root," and manifest with different degrees of Life (or energy), Consciousness, and Matter.[c]

The second proposition is "the absolute universality of that law of periodicity, of flux and reflux, ebb and flow". Accordingly, manifest existence is an eternally re-occurring event on a "boundless plane": "'the playground of numberless Universes incessantly manifesting and disappearing,'"[7] each one "standing in the relation of an effect as regards its predecessor, and being a cause as regards its successor",[8] doing so over vast but finite periods of time.[d]

Related to the above is the third proposition: "The fundamental identity of all Souls with the Universal Over-Soul... and the obligatory pilgrimage for every Soul—a spark of the former—through the Cycle of Incarnation (or 'Necessity') in accordance with Cyclic and Karmic law, during the whole term." The individual souls are seen as units of consciousness (Monads) that are intrinsic parts of a universal oversoul, just as different sparks are parts of a fire. These Monads undergo a process of evolution where consciousness unfolds and matter develops. This evolution is not random, but informed by intelligence and with a purpose. Evolution follows distinct paths in accord with certain immutable laws, aspects of which are perceivable on the physical level. One such law is the law of periodicity and cyclicity; another is the law of karma or cause and effect.[10]

Theories on human evolution and race[edit]

In the second volume of The Secret Doctrine, dedicated to anthropogenesis, Blavatsky presents a theory of the gradual evolution of physical humanity over a timespan of millions of years. The steps in this evolution are called rootraces, seven in all. Earlier rootraces exhibited completely different characteristics: physical bodies first appearing in the second rootrace and sexual characteristics in the third.Some detractors have emphasized passages and footnotes that claim some peoples to be less fully human or spiritual than the "Aryans". For example,

- "Mankind is obviously divided into god-informed men and lower human creatures. The intellectual difference between the Aryan and other civilized nations and such savages as the South Sea Islanders, is inexplicable on any other grounds. No amount of culture, nor generations of training amid civilization, could raise such human specimens as the Bushmen, the Veddhas of Ceylon, and some African Tribes, to the same intellectual level as the Aryans, the Semites, and the Turanians so called. The 'sacred spark' is missing in them and it is they who are the only inferior races on the globe, now happily – owing to the wise adjustment of nature which ever works in that direction – fast dying out. Verily mankind is 'of one blood,' but not of the same essence. We are the hot-house, artificially quickened plants in nature, having in us a spark, which in them is latent" (The Secret Doctrine, Vol. 2, p 421).

- "Of such semi-animal creatures, the sole remnants known to Ethnology were the Tasmanians, a portion of the Australians and a mountain tribe in China, the men and women of which are entirely covered with hair. They were the last descendants in a direct line of the semi-animal latter-day Lemurians referred to. There are, however, considerable numbers of the mixed Lemuro-Atlantean peoples produced by various crossings with such semi-human stocks – e.g., the wild men of Borneo, the Veddhas of Ceylon, classed by Prof. Flower among Aryans (!), most of the remaining Australians, Bushmen, Negritos, Andaman Islanders, etc" (The Secret Doctrine, Vol. 2, pp 195–6).

- "Esoteric history teaches that idols and their worship died out with the Fourth Race, until the survivors of the hybrid races of the latter (Chinamen, African negroes, &c.) gradually brought the worship back. The Vedas countenance no idols; all the modern Hindu writings do" (The Secret Doctrine, Vol. 2, p 723).

She also prophesies of the destruction of the racial "failures of nature" as the "higher race" ascends:

- "Thus will mankind, race after race, perform its appointed cycle-pilgrimage. Climates will, and have already begun, to change, each tropical year after the other dropping one sub-race, but only to beget another higher race on the ascending cycle; while a series of other less favoured groups – the failures of nature – will, like some individual men, vanish from the human family without even leaving a trace behind" (The Secret Doctrine, Vol. 2, p 446).

Study of the Secret Doctrine[edit]

According to PGB Bowen, Blavatsky gave the following instructions regarding the study of the Secret Doctrine:Reading the SD page by page as one reads any other book (she says) will only end us in confusion. The first thing to do, even if it takes years, is to get some grasp of the 'Three Fundamental Principles' given in the Proem. Follow that up by study of the Recapitulation – the numbered items in the Summing Up to Vol. I (Part 1.) Then take the Preliminary Notes (Vol. II) and the Conclusion (Vol. II)[11]

Writings about "The Secret Doctrine"[edit]

- Alice Bailey: "But those of us who really studied it and arrived at some understanding of its inner significance have a basic appreciation of the truth that no other book seems to supply. HPB said that the next interpretation of the Ageless Wisdom would be a psychological approach, and A Treatise on Cosmic Fire, which I published in 1925, is the psychological key to The Secret Doctrine. None of my books would have been possible had I not at one time made a very close study of The Secret Doctrine."[12]

- Blavatsky and The Secret Doctrine by Max Heindel (1933; from Max Heindel writings & with introduction by Manly Palmer Hall): "The Secret doctrine is one of the most remarkable books in the world... Behind her [H.P.B.] stood the real teachers, the guardians of the Secret Wisdom of the ages, who taught her all the occult lore which she transmitted in her writings."[full citation needed]

Critical reception[edit]

Historian Ronald H. Fritze has written that The Secret Doctrine presents a "series of far-fetched ideas unsupported by any reliable historical or scientific research."[13] According to Fritze:Unfortunately the factual basis for Blavatsky's book is nonexistent. She claimed to have received her information during trances in which the Masters of Mahatmas of Tibet communicated with her and allowed her to read from the ancient Book of Dzyan. The Book of Dzyan was supposedly composed in Atlantis using the lost language of Senzar but the difficulty is that no scholar of ancient languages in the 1880s or since has encountered the slightest passing reference to the Book of Dzyan or the Senzar language.[13]Scholars and skeptics have criticized The Secret Doctrine for plagiarism.[14] It is said to have been heavily influenced by occult and oriental works.[15][16]

L. Sprague de Camp in his book Lost Continents has written that Blavatsky's main sources were "H. H. Wilson's translation of the ancient Indian Vishnu Purana; Alexander Winchell's World Life; or, Comparative Geology; Donnelly's Atlantis; and other contemporary scientific, pseudo-scientific, and occult works, plagiarized without credit and used in a blundering manner that showed but skin-deep acquaintance with the subjects under discussion."[17] Camp described the book as a "mass of plagiarism and fakery."[18]

The book has also been accused of antisemitism and criticized for its emphasis on race. Historian Hannah Newman has noted that the book "denigrates the Jewish faith as harmful to human spirituality".[19] Historian Michael Marrus has written that Blavatsky's racial ideas "could be easily misused" and that her book had helped to foster antisemitism in Germany during World War II.[20]

See also[edit]

- Book of Dzyan

- Mahatma Letters

- Man: Whence, How and Whither

- New Age Spirituality

- New Thought

- The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception

- Round (Theosophy)

- Theosophy

- Isis Unveiled

Notes[edit]

- Jump up ^ "An Omnipresent, Eternal, Boundless, and Immutable PRINCIPLE on which all speculation is impossible, since it transcends the power of human conception and could only be dwarfed by any human expression or similitude."[3]

- Jump up ^ "The expansion 'from within without'..., does not allude to an expansion from a small centre or focus, but, without reference to size or limitation or area, means the development of limitless subjectivity into as limitless objectivity. ...It implies that this expansion, not being an increase in size—for infinite extension admits of no enlargement—was a change of condition." Manifest existence is often called "Illusion" in Theosophy, owing to its conceptual and actual differentiation from the only Reality.[5]

- Jump up ^ "Everything in the Universe, throughout all its kingdoms, is CONSCIOUS: i.e., endowed with a consciousness of its own kind and on its own plane of perception. We men must remember that because we do not perceive any signs—which we can recognise—of consciousness, say, in stones, we have no right to say that no consciousness exists there. There is no such thing as either 'dead' or 'blind' matter, as there is no 'Blind' or 'Unconscious' Law".[6]

- Jump up ^ Blavatsky states that each complete cycle lasts 311,040,000,000,000 years.[9]

References[edit]

- Jump up ^ Blavatsky 1888a, pp. 272–274.

- Jump up ^ Blavatsky 1888b, pp. 185–187.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Blavatsky 1888a, p. 14.

- Jump up ^ Blavatsky 1888a, pp. 35–85.

- Jump up ^ Blavatsky 1888a, pp. 62–63.

- Jump up ^ Blavatsky 1888a, p. 274.

- Jump up ^ Blavatsky 1888a, p. 17.

- Jump up ^ Blavatsky 1888a, p. 43.

- Jump up ^ Blavatsky 1888a, p. 206.

- Jump up ^ Blavatsky 1888a, pp. 274–275.

- Jump up ^ Bowen 1988.

- Jump up ^ Bailey, Alice A., "Chapter VI", The Unfinished Autobiography, Lucis Trust

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fritze, Ronald H. (2009). Invented Knowledge: False History, Fake Science and Pseudo-Religions. Reaktion Books. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-1-86189-430-4

- Jump up ^ Floyd, E. Randall. (2005). The Good, the Bad and the Mad: Some Weird People in American History. Fall River Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0760766002 "Scholars and critics were quick to claim that much of the work was stolen from books by other occultists and crank scholars like Ignatius Loyola Donnelly's book on Atlantis."

- Jump up ^ Cohen, Daniel. (1989). Encyclopedia of the Strange. Marboro Books. p. 108. ISBN 978-0380702688 "When the book was finally published, critics snickered, Oriental scholars were outraged, and other scholars pointed out that the work was largely stolen from books by other occultists and crank scholars like Ignatius Donnelly's book on Atlantis."

- Jump up ^ Sedgwick, Mark. (2004). Against the Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-19-515297-2 "The Secret Doctrine drew heavily on John Dowson's Classical Dictionary of Hindu Mythology and Religion, Horace Wilson's annotated translation of the Vishnu Purana, and other such works."

- Jump up ^ L. Sprague de Camp. (1970). Lost Continents. Dover Publications. p. 57. ISBN 0-486-22668-9 "The Secret Doctrine, alas, is neither so ancient, so erudite, nor so authentic as it pretends to be. When it appeared, an elderly Californian scholar named William Emmette Coleman, outraged by Mme. Blavatsky's false pretensions to oriental learning, made an exegesis of her works. He showed that her main sources were H. H. Wilson's translation of the ancient Indian Vishnu Purana; Alexander Winchell's World Life; or, Comparative Geology; Donnelly's Atlantis; and other contemporary scientific, pseudo-scientific, and occult works, plagiarized without credit and used in a blundering manner that showed but skin-deep acquaintance with the subjects under discussion."

- Jump up ^ L. Sprague de Camp. The Fringe of the Unknown. Prometheus Books. p. 193. ISBN 0-87975-217-3 "Three years later, she published her chef d'oeuvre, The Secret Doctrine, in which her credo took permanent, if wildly confused, shape. This work, in six volumes, is a mass of plagiarism and fakery, based upon contemporary scientific, pseudoscientific, mythological, and occult works, cribbed without credit and used in a blundering way that showed only skin-deep acquaintance with the subjects discussed."

- Jump up ^ Newman, Hannah. Blavatsky, Helena P. (1831-1891) . In Richard S. Levy. (2005). Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution. ABC-CLIO. p. 73. ISBN 1-85109-439-3

- Jump up ^ Marrus, Michael. (1989). The Origins of the Holocaust. Meckler. pp. 85–87. ISBN 0-88736-253-2 "In her esoteric work, especially The Secret Doctrine, originally published in 1888, Blavatsky emphasized the concept of races as paramount in the development of human history... Blavatsky herself did not identify the Aryan race with the Germanic peoples. And although her racial doctrine clearly entailed belief in superior and inferior races and hence could be easily misused, she placed no emphasis on the domination of one race over another... Nevertheless, in her work Blavatsky had helped to foster antisemitism, which is perhaps one the reasons her esoteric work was so rapidly accepted in Germanic circles."

Bibliography[edit]

- Blavatsky, HP (1888a), The Secret Doctrine.

- Blavatsky, HP (1888b), The First Message to WQ Judge, General Secretary of the American Section of the Theosophical Society.

- Blavatsky, HP, The Key to Theosophy.

- Bowen, PGB (15 November 2010), The Secret Doctrine and Its Study, Pasadena: The Society Check date values in:

|year= / |date= mismatch(help). - Heindel, Max (1933), Blavatsky and The Secret Doctrine (essay), Rosicrucian zine, introduction by Manly Palmer Hall.

- Keightley, Archibald Account of the Writing of "The Secret Doctrine".

- Kuhn, Alvin Boyd (1930) Theosophy: A Modern Revival of Ancient Wisdom, PhD Thesis. Whitefish, Montana: Kessinger Publishing. Chap. viii "The Secret Doctrine", pp. 193–230. ISBN 9781564591753.

- Wachtmeister, Constance Reminiscences of H.P. Blavatsky and "The Secret Doctrine".

- Сенкевич, Александр Николаевич (2012) Елена Блаватская. Между светом и тьмой – М.: Алгоритм. Гл. "Тайная доктрина", стр. 455–462. ISBN 9785443802374.