From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia/Blogger Ref http://www.p2pfoundation.net/Multi-Dimensional_Science

(Redirected from Tetraktys)

Contents

[hide]Pythagorean symbol[edit]

- The first four numbers symbolize the harmony of the spheres and the Cosmos as:

- The four rows add up to ten, which was unity of a higher order (The Dekad).

- The Tetractys symbolizes the four elements—fire, air, water, and earth.

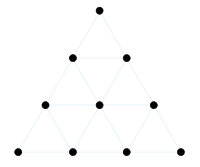

- The Tetractys represented the organization of space:

- the first row represented zero dimensions (a point)

- the second row represented one dimension (a line of two points)

- the third row represented two dimensions (a plane defined by a triangle of three points)

- the fourth row represented three dimensions (a tetrahedron defined by four points)

- "Bless us, divine number, thou who generated gods and men! O holy, holy Tetractys, thou that containest the root and source of the eternally flowing creation! For the divine number begins with the profound, pure unity until it comes to the holy four; then it begets the mother of all, the all-comprising, all-bounding, the first-born, the never-swerving, the never-tiring holy ten, the keyholder of all".[3]

The Pythagorean oath also mentioned the Tetractys:

- "By that pure, holy, four lettered name on high,

- nature's eternal fountain and supply,

- the parent of all souls that living be,

- by him, with faith find oath, I swear to thee."

Quotation:

- "The Tetractys [also known as the decad] is an equilateral triangle formed from the sequence of the first ten numbers aligned in four rows. It is both a mathematical idea and a metaphysical symbol that embraces within itself—in seedlike form—the principles of the natural world, the harmony of the cosmos, the ascent to the divine, and the mysteries of the divine realm. So revered was this ancient symbol that it inspired ancient philosophers to swear by the name of the one who brought this gift to humanity."

Kabbalist symbol[edit]

Symbol by early 17th-century Christian mystic Jakob Böhme, including a tetractys of flaming Hebrew letters of the Tetragrammaton.

- "The point is assigned to Kether;

- the line to Chokmah;

- the two-dimensional plane to Binah;

- consequently the three-dimensional solid naturally falls to Chesed."[9]

The relationship between geometrical shapes and the first four Sephirot is analogous to the geometrical correlations in Tetraktys, shown above under Pythagorean Symbol, and unveils the relevance of the Tree of Life with the Tetraktys.

Tarot card reading arrangement[edit]

In a Tarot reading, the various positions of the tetractys provide a representation for forecasting future events by signifying according to various occult disciplines, such as Alchemy. [1] Below is only a single variation for interpretation.The first row of a single position represents the Premise of the reading, forming a foundation for understanding all the other cards.

The second row of two positions represents the cosmos and the individual and their relationship.

- The Light Card to the right represents the influence of the cosmos leading the individual to an action.

- The Dark Card to the left represents the reaction of the cosmos to the actions of the individual.

- The Creator Card is rightmost, representing new decisions and directions that may be made.

- The Sustainer Card is in the middle, representing decisions to keep balance, and things that should not change.

- The Destroyer Card is leftmost, representing old decisions and directions that should not be continued.

- The Fire card is rightmost, representing dynamic creative force, ambitions, and personal will.

- The Air card is to the right middle, representing the mind, thoughts, and strategies toward goals.

- The Water card is to the left middle, representing the emotions, feelings, and whims.

- The Earth card is leftmost, representing physical realities of day to day living.

Occurrence[edit]

- the baryon decuplet

- an archbishop's coat of arms

- the arrangement of pins in ten-pin bowling

- a Chinese checkers board

Tetractys in poetry[edit]

In English-language poetry, a tetractys is a syllable-counting form with five lines. The first line has one syllable, the second has two syllables, the third line has three syllables, the fourth line has four syllables, and the fifth line has ten syllables. [10] A sample tetractys would look like this:- Mantrum

- Your /

- fury /

- confuses /

- us all greatly. /

- Volatile, big-bodied tots are selfish. //

- "The tetractys could be Britain's answer to the haiku. Its challenge is to express a complete thought, profound or comic, witty or wise, within the narrow compass of twenty syllables."[11]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- Jump up ^ The Theosophical Glossary, p. 302

- Jump up ^ The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library by Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie

- Jump up ^ Dantzig, Tobias ([1930], 2005) Number. The Language of Science. p. 42

- Jump up ^ Introduction to Arithmetic – Nicomachus of Gerasa

- Jump up ^ The Musical Order of the World: Kepler, Hesse, Hindemith-Siglind Bruhn

- Jump up ^ A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities(1890) – William Smith, LLD, William Wayte, G. E. Marindin, Ed.

- Jump up ^ Plutarch, De animae procreatione in Timaeo – Goodwin, Ed.(lang.:English)

- Jump up ^ Sacred Architecture of London – Nigel Pennick

- Jump up ^ The Mystical Qabalah, Dion Fortune, Chapter XVIII, 25

- Jump up ^ English Syllable Counters

- Jump up ^ Tetractys

Further reading[edit]

- von Franz, Marie-Louise. Number and Time: Reflections Leading Towards a Unification of Psychology and Physics. Rider & Company, London, 1974. ISBN 0-09-121020-8

- Fideler, D. ed. The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library. Phanes Press, 1987.

- The Theoretic Arithmetic of the Pythagoreans – Thomas Taylor