Fold-up geometrical illustrations in the first English edition of Euclid’s ‘Elements of Geometry,’ published London, 1570. John Dee wrote a mathematical preface to the book. (© Royal College of Physicians)

A rotating paper volvelle used as a cipher disc in Johannes Trithemius’ cryptographic book ‘Polygraphy,’ published Paris, 1561. This book was owned by John Dee (© Royal College of Physicians)

“Today we tend to think of magic as being something quite separate from, indeed the exact opposite of, science,” Katie Birkwood, rare books and special collections librarian at the Royal College of Physicians and The Lost Library of John Dee curator, told Hyperallergic. “In Tudor England, the distinctions between magic and natural philosophy — as the subject we now think of science would have been termed then — were not nearly so clear cut. A keen interest in subjects such as mathematics could sometimes be seen as threatening and magical to Tudor eyes.”

“Lost Library” of John Dee books (courtesy RCP and John Chase)

John Dee’s crystal, used for clairvoyance and for curing disease (courtesy Science Museum, London / Wellcome Images) (click to enlarge)

So while the books on view were never “lost,” Dee’s connection, and especially the inclusion of his occult objects, is something being emphasized in this exhibition for the first time. Much of the research for The Lost Library of John Dee focuses on annotations in his books, where he marked important passages, scratched out horoscopes, mused on alchemy, and even chronicled some biographical information.

The books also represent the complications of practicing magic in Tudor England, where it was both sometimes accepted, but often dangerous. Dee had a copy of a treatise by the Italian astrologer and physician Cardano, with horoscopes alongside biographical information about himself, his family, and a patron, yet it was the 1555 horoscope calculation for Mary I that got him arrested.

“Astrology, an arguably magical practice, was widely used at the time by people of all social status,” Birkwood stated. “However, it did not occupy a stable position in society. An astrologer — someone adept at measuring, plotting and interpreting the positions of the stars and planets — could be viewed with suspicion, hostility and fear because it could be felt that their knowledge and skills gave them access to too much information about people and events.”

Later, he did become the conjuror to Queen Elizabeth I, and his legacy is now a magician who fused scientific knowledge with a curiosity about the supernatural, a delicate balance of two sides of the Tudor age.

John Dee Ashmolean Portrait (artist unknown) (1594) (© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

Claude Lorrain mirror in shark skin case, believed at one time to be John Dee’s scrying mirror. (courtesy Science Museum, London / Wellcome Images)

Henry Gillard Glindoni,” John Dee performing an experiment before Queen Elizabeth I” (late 19th century) (courtesy National Gallery, London/Wellcome Library, London)

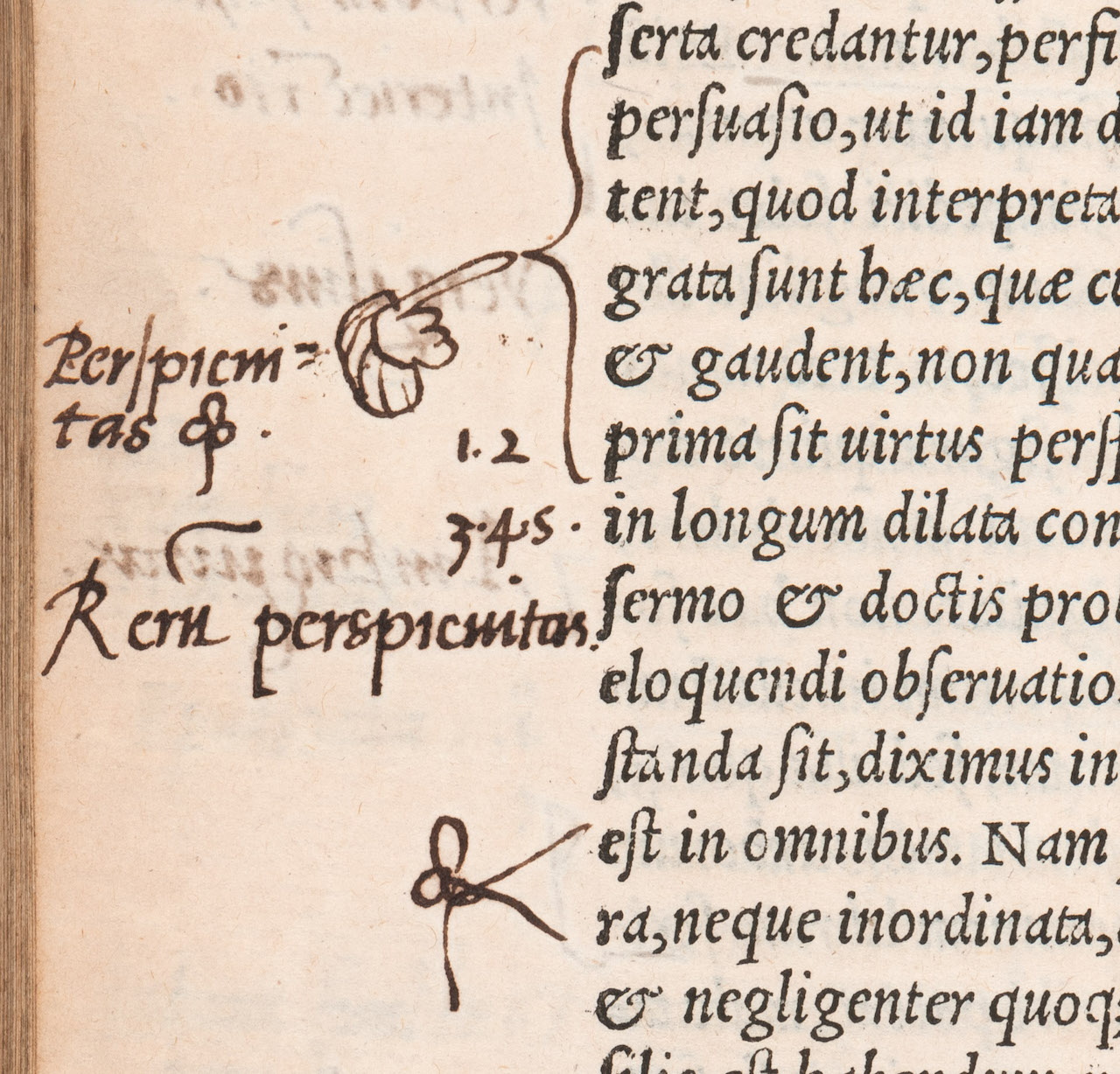

A small pointing hand — known as a manicule — drawn in the margin of a book of classical rhetoric, owned and heavily annotated by John Dee. (Quintilian, ‘Institutionum oratoriarum,’ published Lyon, 1540) (© Royal College of Physicians / Mike Fear)

A ship sweeps on the waves at the corner of a page of the complete works of Cicero. John Dee was likely inspired by the adjoining lines of verse: “So huge a bulk glides from the deep with the roar of a whistling wind / Waves roll before, and eddies surge and swirl / Hurtling headlong, it snorts and sprays the foam.” (Cicero, ‘Opera,’ published Paris, 1539–1540) (© Royal College of Physicians / John Chase)

A horoscope chart jotted by John Dee in the margin of an ancient treatise on the power and influence of the heaves. (Claudius Ptolemy, ‘Quadriparti,’ published Venice, 1519) (© Royal College of Physicians / John Chase)

Two attempts at a horoscope chart, drawn in haste by John Dee in the margins of a book about astrology. (Girolamo Cardano, ‘Libelli quinque,’ published Nuremberg, 1547) (© Royal College of Physicians / John Chase)

A sketch of alchemical equipment — an alembic — drawn and signed by John Dee in the margins of an alchemical treatise. (Petrus Bonus (attrib), ‘Introductio in divinam chemiae artem integra,’ published Basel, 1572) (© Royal College of Physicians / Mike Fear)

Doodles by John Dee in the margins of Cicero’s work ‘De legibus,’ relating to the worship of gods, and the Persian king Xerxes setting fire to Greek temples. (Cicero, ‘Opera,’ published Paris, 1539–1540) (© Royal College of Physicians / Mike Fear)

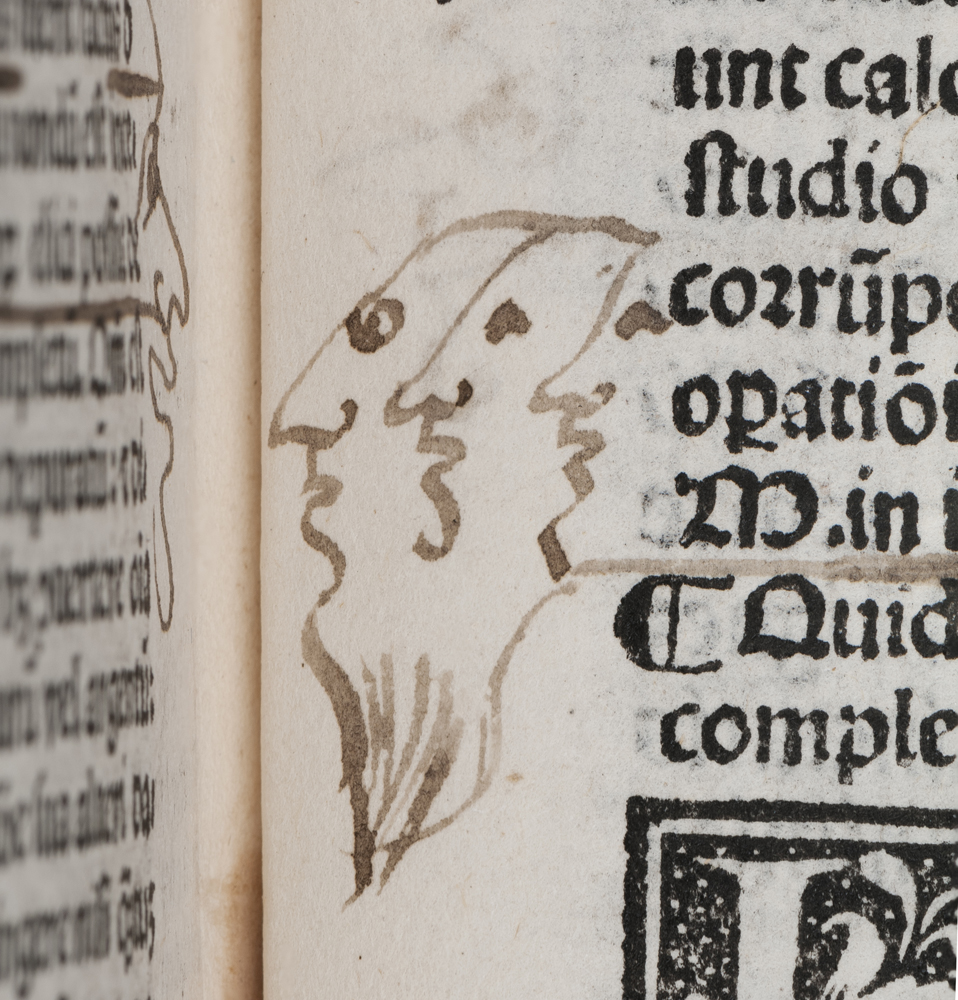

John Dee’s doodle of three bearded faces in the margin of a treatise on alchemy (Arnaldus de Villanova, ‘Opera,’ published Venice, 1527) (© Royal College of Physicians / Mike Fear)

No comments:

Post a Comment