From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia/Blogger Ref http://www.p2pfoundation.net/Multi-Dimensional_Science

(Redirected from Mystical)

This article is about mystical traditions. For mystical experience, see mystical experience.

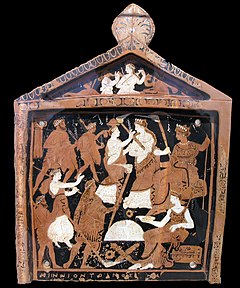

Votive plaque depicting elements of the Eleusinian Mysteries, discovered in the sanctuary at Eleusis (mid-4th century BC)

| Part of a series on |

| Spirituality |

|---|

| Influences |

| Part of a series on |

| Universalism |

|---|

|

| Category |

The term "mysticism" has Ancient Greek origins with various historically determined meanings.[web 2][web 1] Derived from the Greek word μυω, meaning "to conceal",[web 1] mysticism referred to the biblical liturgical, spiritual, and contemplative dimensions of early and medieval Christianity.[1] During the early modern period, the definition of mysticism grew to include a broad range of beliefs and ideologies related to "extraordinary experiences and states of mind".[2]

In modern times, "mysticism" has acquired a limited definition,[web 2] with broad applications,[web 2] as meaning the aim at the "union with the Absolute, the Infinite, or God".[web 2] This limited definition has been applied to a wide range of religious traditions and practices,[web 2] valuing "mystical experience" as a key element of mysticism.

Since the 1960s scholars have debated the merits of perennial and constructionist approaches in the scientific research of "mystical experiences";[3][4] the perennial position is now "largely dismissed by scholars".[5]

Contents

[hide]Etymology[edit]

"Mysticism" is derived from the Greek μυω, meaning "I conceal",[web 1] and its derivative μυστικός, mystikos, meaning 'an initiate'.Definitions[edit]

Parson warns that "what might at times seem to be a straightforward phenomenon exhibiting an unambiguous commonality has become, at least within the academic study of religion, opaque and controversial on multiple levels".[6] The definition, or meaning, of the term "mysticism" has changed through the ages.[web 2]Spiritual life and re-formation[edit]

Main article: Spirituality

According to Evelyn Underhill, mysticism is "the science or art of the spiritual life."[7] It is...the expression of the innate tendency of the human spirit towards complete harmony with the transcendental order; whatever be the theological formula under which that order is understood.[8][note 1][note 2]Parson stresses the importance of distinguishing between

...episodic experience and mysticism as a process that, though surely punctuated by moments of visionary, unitive, and transformative encounters, is ultimately inseparable from its embodied relation to a total religious matrix: liturgy, scripture, worship, virtues, theology, rituals, practice and the arts.[9]According to Gellmann,

Typically, mystics, theistic or not, see their mystical experience as part of a larger undertaking aimed at human transformation (See, for example, Teresa of Avila, Life, Chapter 19) and not as the terminus of their efforts. Thus, in general, ‘mysticism’ would best be thought of as a constellation of distinctive practices, discourses, texts, institutions, traditions, and experiences aimed at human transformation, variously defined in different traditions.[web 1][note 3]McGinn argues that "presence" is more accurate than "union", since not all mystics spoke of union with God, and since many visions and miracles were not necessarily related to union. He also argues that we should speak of "consciousness" of God's presence, rather than of "experience", since mystical activity is not simply about the sensation of God as an external object, but more broadly about

...new ways of knowing and loving based on states of awareness in which God becomes present in our inner acts.[12]D.J. Moores too mentions "love" as a central element:

Mysticism, then, is the perception of the universe and all of its seemingly disparate entities existing in a unified whole bound together by love.[13]Related to the idea of "presence" instead of "experience" is the transformation that occurs through mystical activity:

This is why the only test that Christianity has known for determining the authenticity of a mystic and her or his message has been that of personal transformation, both on the mystic's part and—especially—on the part of those whom the mystic has affected.[12]Belzen and Geels also note that mysticism is

...a way of life and a 'direct consciousness of the presence of God' [or] 'the ground of being' or similar expressions.[14]

Enlightenment[edit]

Main article: Enlightenment (spiritual)

Some authors emphasize that mystical experience involves intuitive understanding and the resolution of life problems. According to Larson,A mystical experience is an intuitive understanding and realization of the meaning of existence – an intuitive understanding and realization which is intense, integrating, self-authenticating, liberating – i.e., providing a sense of release from ordinary self-awareness – and subsequently determinative – i.e., a primary criterion – for interpreting all other experience whether cognitive, conative, or affective.[15]And James R. Horne notes:

[M]ystical illumination is interpreted as a central visionary experience in a psychological and behavioural process that results in the resolution of a personal or religious problem. This factual, minimal interpretation depicts mysticism as an extreme and intense form of the insight seeking process that goes in activities such as solving theoretical problems or developing new inventions.[3][note 4][note 5]

Mystical experience and union with the Divine[edit]

William James, who popularized the use of the term "religious experience"[note 6] in his The Varieties of Religious Experience,[19][20][web 1] influenced the understanding of mysticism as a distinctive experience which supplies knowledge of the transcendental.[21][web 1] He considered the "personal religion"[22] to be "more fundamental than either theology or ecclesiasticism",[22] and states:In mystic states we both become one with the Absolute and we become aware of our oneness. This is the everlasting and triumphant mystical tradition, hardly altered by differences of clime or creed. In Hinduism, in Neoplatonism, in Sufism, in Christian mysticism, in Whitmanism, we find the same recurring note, so that there is about mystical utterances an eternal unanimity which ought to make a critic stop and think, and which bring it about that the mystical classics have, as been said, neither birthday not native land.[23]According to McClenon, mysticism is

The doctrine that special mental states or events allow an understanding of ultimate truths. Although it is difficult to differentiate which forms of experience allow such understandings, mental episodes supporting belief in "other kinds of reality" are often labeled mystical [...] Mysticism tends to refer to experiences supporting belief in a cosmic unity rather than the advocation of a particular religious ideology.[web 3]According to Blakemore and Jennett,

Mysticism is frequently defined as an experience of direct communion with God, or union with the Absolute,[note 7] but definitions of mysticism (a relatively modern term) are often imprecise and usually rely on the presuppositions of the modern study of mysticism — namely, that mystical experiences involve a set of intense and usually individual and private psychological states [...] Furthermore, mysticism is a phenomenon said to be found in all major religious traditions.[web 4][note 8]

History[edit]

Early Christianity[edit]

In the Hellenistic world, 'mystical' referred to "secret" religious rituals[web 1] The use of the word lacked any direct references to the transcendental.[25] A "mystikos" was an initiate of a mystery religion.In early Christianity the term "mystikos" referred to three dimensions, which soon became intertwined, namely the biblical, the liturgical and the spiritual or contemplative.[1] The biblical dimension refers to "hidden" or allegorical interpretations of Scriptures.[web 1][1] The liturgical dimension refers to the liturgical mystery of the Eucharist, the presence of Christ at the Eucharist.[web 1][1] The third dimension is the contemplative or experiential knowledge of God.[1]

The link between mysticism and the vision of the Divine was introduced by the early Church Fathers, who used the term as an adjective, as in mystical theology and mystical contemplation.[25]

Medieval meaning[edit]

See also: Middle Ages

This threefold meaning of "mystical" continued in the Middle Ages.[1] Under the influence of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite the mystical theology came to denote the investigation of the allegorical truth of the Bible.[1] Pseudo-Dionysius' Apophatic theology, or "negative theology", exerted a great influence on medieval monastic religiosity, although it was mostly a male religiosity, since women were not allowed to study.[26] It was influenced by Neo-Platonism, and very influential in Eastern Orthodox Christian theology. In western Christianity it was a counter-current to the prevailing Cataphatic theology or "positive theology". It is best known nowadays in the western world from Meister Eckhart and John of the Cross.Early modern meaning[edit]

See also: Early modern period

The Appearance of the Holy Spirit before Saint Teresa of Ávila, Peter Paul Rubens

Luther dismissed the allegorical interpretation of the bible, and condemned Mystical theology, which he saw as more Platonic than Christian.[28] "The mystical", as the search for the hidden meaning of texts, became secularised, and also associated with literature, as opposed to science and prose.[29]

Science was also distinguished from religion. By the middle of the 17th century, "the mystical" is increasingly applied exclusively to the religious realm, separating religion and "natural philosophy" as two distinct approaches to the discovery of the hidden meaning of the universe.[30] The traditional hagiographies and writings of the saints became designated as "mystical", shifting from the virtues and miracles to extraordinary experiences and states of mind, thereby creating a newly coined "mystical tradition".[2] A new understanding developed of the Divine as residing within human, an essence beyond the varieties of religious expressions.[25]

Contemporary meaning[edit]

In the 19th century the meaning of mysticism was considerably narrowed:[web 2]The competition between the perspectives of theology and science resulted in a compromise in which most varieties of what had traditionally been called mysticism were dismissed as merely psychological phenomena and only one variety, which aimed at union with the Absolute, the Infinite, or God—and thereby the perception of its essential unity or oneness—was claimed to be genuinely mystical. The historical evidence, however, does not support such a narrow conception of mysticism.[web 2]Under the influence of Perennialism, which was popularised in both the west and the east by Unitarianism, Transcendentalists and Theosophy, mysticism has acquired a broader meaning, in which all sorts of esotericism and religious traditions and practices are joined together.[31][32][20]

The term mysticism has been extended to comparable phenomena in non-Christian religions,[web 2] where it influenced Hindu and Buddhist responses to colonialism, resulting in Neo-Vedanta and Buddhist modernism.[32][33]

In the contemporary usage "mysticism" has become an umbrella term for all sorts of non-rational world views.[34] William Harmless even states that mysticism has become "a catch-all for religious weirdness".[35] Within the academic study of religion the apparent "unambiguous commonality" has become "opaque and controversial".[25] The term "mysticism" is being used in different ways in different traditions.[25] Some call to attention the conflation of mysticism and linked terms, such as spirituality and esotericism, and point at the differences between various traditions.[36]

Mystical experience[edit]

Main article: Mystical experience

Since the 19th century, "mystical experience" has evolved as a distinctive concept. It is closely related to "mysticism," but lays sole emphasis on the experiential aspect, be it spontaneous or induced by human behavior.Two distinct approaches can be discerned in the study of mystical experience. Perennialists regard those various traditions as pointing to one universal transcendental reality, for which those experiences offer the prove.

The perennial position is "largely dismissed by scholars",[5] but "has lost none of its popularity".[37] Instead, a constructionist approach is favored, which states that mystical experiences are mediated by pre-existing frames of reference. Critics of the term "religious experience" note that the notion of "religious experience" or "mystical experience" as marking insight into religious truth is a modern development,[38] and contemporary researchers of mysticism note that mystical experiences are shaped by the concepts "which the mystic brings to, and which shape, his experience".[39] What is being experienced is being determined by the expectations and the conceptual background of the mystic.[40]

Forms of mysticism within world religions[edit]

Based on various definitions of mysticism, namely mysticism as a way of transformation, mysticism as "enlightenment" or insight, and mysticism as an experience of union, "mysticism" can be found an all major world religions.Western mysticism[edit]

Mystery religions[edit]

Main article: Greco-Roman mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries, (Greek: Ἐλευσίνια Μυστήρια) were annual initiation ceremonies in the cults of the goddesses Demeter and Persephone, held in secret at Eleusis (near Athens) in ancient Greece.[41] The mysteries began in about 1600 B.C. in the Mycenean period and continued for two thousand years, becoming a major festival during the Hellenic era, and later spreading to Rome.[42]Christian mysticism[edit]

The Apophatic theology, or "negative theology",of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite exerted a great influence on medieval monastic religiosity.[26]The High Middle Ages saw a flourishing of mystical practice and theorization corresponding to the flourishing of new monastic orders, with such figures as Guigo II, Hildegard of Bingen, Bernard of Clairvaux, the Victorines, all coming from different orders, as well as the first real flowering of popular piety among the laypeople.

The Late Middle Ages saw the clash between the Dominican and Franciscan schools of thought, which was also a conflict between two different mystical theologies: on the one hand that of Dominic de Guzmán and on the other that of Francis of Assisi, Anthony of Padua, Bonaventure, and Angela of Foligno. This period also saw such individuals as John of Ruysbroeck, Catherine of Siena and Catherine of Genoa, the Devotio Moderna, and such books as the Theologia Germanica, The Cloud of Unknowing and The Imitation of Christ.

Moreover, there was the growth of groups of mystics centered around geographic regions: the Beguines, such as Mechthild of Magdeburg and Hadewijch (among others); the Rhineland mystics Meister Eckhart, Johannes Tauler and Henry Suso; and the English mystics Richard Rolle, Walter Hilton and Julian of Norwich. The Spanish mystics included Teresa of Avila, John of the Cross and Ignatius Loyola.

The later post-reformation period also saw the writings of lay visionaries such as Emanuel Swedenborg and William Blake, and the foundation of mystical movements such as the Quakers. Catholic mysticism continued into the modern period with such figures as Padre Pio and Thomas Merton.

The philokalia, an ancient method of Eastern Orthodox mysticism, was promoted by the twentieth century Traditionalist School. The inspired or "channeled" work A Course in Miracles represents a blending of non-denominational Christian and New Age ideas.

Jewish mysticism[edit]

| Jewish mysticism |

|---|

|

Main articles: Jewish mysticism and Kabbalah

In the common era, Judaism has had two main kinds of mysticism: Merkabah mysticism and Kabbalah. The former predated the latter, and was focused on visions, particularly those mentioned in the Book of Ezekiel. It gets its name from the Hebrew word meaning "chariot", a reference to Ezekiel's vision of a fiery chariot composed of heavenly beings.Kabbalah is a set of esoteric teachings meant to explain the relationship between an unchanging, eternal and mysterious Ein Sof (no end) and the mortal and finite universe (his creation). Inside Judaism, it forms the foundations of mystical religious interpretation.

Kabbalah originally developed entirely within the realm of Jewish thought. Kabbalists often use classical Jewish sources to explain and demonstrate its esoteric teachings. These teachings are thus held by followers in Judaism to define the inner meaning of both the Hebrew Bible and traditional Rabbinic literature, their formerly concealed transmitted dimension, as well as to explain the significance of Jewish religious observances.[43]

Kabbalah emerged, after earlier forms of Jewish mysticism, in 12th to 13th century Southern France and Spain, becoming reinterpreted in the Jewish mystical renaissance of 16th-century Ottoman Palestine. It was popularised in the form of Hasidic Judaism from the 18th century forward. 20th-century interest in Kabbalah has inspired cross-denominational Jewish renewal and contributed to wider non-Jewish contemporary spirituality, as well as engaging its flourishing emergence and historical re-emphasis through newly established academic investigation.

Islamic mysticism[edit]

| [hide] Sufism and Tariqat |

|---|

|

Main article: Sufism

Sufism is said to be Islam's inner and mystical dimension.[44][45][46] Classical Sufi scholars have defined Sufism as[A] science whose objective is the reparation of the heart and turning it away from all else but God.[47]A practitioner of this tradition is nowadays known as a ṣūfī (صُوفِيّ), or, in earlier usage, a dervish. The origin of the word "Sufi" is ambiguous. One understanding is that Sufi means wool-wearer- wool wearers during early Islam were pious ascetics who withdrew from urban life. Another explanation of the word "Sufi" is that it means 'purity'.[48]

Sufis generally belong to a khalqa, a circle or group, led by a Sheikh or Murshid. Sufi circles usually belong to a Tariqa which is the Sufi order and each has a Silsila, which is the spiritual lineage, which traces its succession back to notable Sufis of the past, and often ultimately to the prophet Muhammed or one of his close associates. The turuq (plural of tariqa) are not enclosed like Christian monastic orders; rather the members retain an outside life. Membership of a Sufi group often passes down family lines. Meetings may or may not be segregated according to the prevailing custom of the wider society. An existing Muslim faith is not always a requirement for entry, particularly in Western countries.

Sufi practice includes

- Dhikr, or remembrance (of God), which often takes the form of rhythmic chanting and breathing exercises.

- Sema, which takes the form of music and dance — the whirling dance of the Mevlevi dervishes is a form well known in the West.

- Muraqaba or meditation.

- Visiting holy places, particularly the tombs of Sufi saints, in order to absorb barakah, or spiritual energy.

Notable classical Sufis include Jalaluddin Rumi, Fariduddin Attar, Sultan Bahoo, Saadi Shirazi and Hafez, all major poets in the Persian language. Omar Khayyam, Al-Ghazzali and Ibn Arabi were renowned scholars. Abdul Qadir Jilani, Moinuddin Chishti, and Bahauddin Naqshband founded major orders, as did Rumi. Rabia Basri was the most prominent female Sufi.

Sufism first came into contact with the Judea-Christian world during the Moorish occupation of Spain. An interest in Sufism revived in non-Muslim countries during the modern era, led by such figures as Inayat Khan and Idries Shah (both in the UK), Rene Guenon (France) and Ivan Aguéli (Sweden). Sufism has also long been present in Asian countries that do not have a Muslim majority, such as India and China.[49]

Indian religions[edit]

Buddhism[edit]

Main article: Buddhism

The main aim of Buddhism is liberation from the cycle of rebirth, by enlarging self-awareness and self-control. The Buddhist tradition rejects the notion of a permanent self, but does have a strong tradition of metaphysical essentialism, especially Yogacara and the Buddha-nature doctrine. The Madhyamaka tradition lends itself to both a non-metaphysical interpretation, as exemplified by the rangtong philosophy of Tsongkhapa, but also to a "mystical" interpretation, as exemplified by the shentong philosophy of both the Dzogchen tradition and Dolpopa. The Two truths doctrine reconciles absolute and relative reality, but is likewise differently interpreted. Chinese and Japanese is grounded on the Chinse understanding of the Buddha-nature and the Two truths doctrine.[50][51] It was the Japanese Zen-scholar D.T. Suzuki who noted similarities between Buddhism and Christian mysticism.[52]Hinduism[edit]

Main article: Hinduism

Hinduism has a number of interlinked ascetic traditions and philosophical schools which aim at moksha[53] and the acquisition of higher powers.[54] With the onset of the British colonisation of India, those traditions came to be interpreted in western terms such as "mysticism", drawing equivalents with western terms and practices.[55]Yoga is the physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines which aim to attain a state of permanent peace.[56] Various traditions of yoga are found in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.[57][58][59][58] The Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali defines yoga as "the stilling of the changing states of the mind,"[60] which is attained in samadhi.

Classical Vedanta gives philosophical interpretations and commentaries of the Upanishads, a vast collection of ancient hymns. At least ten schools of Vedanta are known,[61] of which Advaita Vedanta, Vishishtadvaita, and Dvaita are the best known.[62] Advaita Vedanta, as expounded by Adi Shankara, states that there is no difference between Atman and Brahman. The best-known subschool is Kevala Vedanta or mayavada as expounded by Adi Shankara. Advaita Vedanta has acquired a broad acceptance in Indian culture and beyond as the paradigmatic example of Hindu spirituality.[63] In contrast Bhedabheda-Vedanta emphasizes that Atamn and Brahman are both the same and not the same,[64] while Dvaita Vedanta states that Atman and God are fundamentally different.[64] In modern times, the Upanishads have been interpreted by Neo-Vedanta as being "mystical".[55]

Various Shaivist traditions are strongly nondualistic, such as Kashmir Shaivism and Shaiva Siddhanta.

Tantra[edit]

Main article: Tantra

Tantra is the name given by scholars to a style of meditation and ritual which arose in India no later than the fifth century AD.[65] Tantra has influenced the Hindu, Bön, Buddhist, and Jain traditions and spread with Buddhism to East and Southeast Asia.[66] Tantric ritual seeks to access the supra-mundane through the mundane, identifying the microcosm with the macrocosm.[67] The Tantric aim is to sublimate (rather than negate) reality.[68] The Tantric practitioner seeks to use prana (energy flowing through the universe, including one's body) to attain goals which may be spiritual, material or both.[69] Tantric practice includes visualisation of deities, mantras and mandalas. It can also include sexual and other (antinomian) practices.[citation needed]Sikhism[edit]

Mysticism in the Sikh dharm began with its founder, Guru Nanak, who as a child had profound mystical experiences.[70] Guru Nanak stressed that God must be seen with 'the inward eye', or the 'heart', of a human being.[71] Guru Arjan, the fifth Sikh Guru, added religious mystics belonging to other religions into the holy scriptures that would eventually become the Guru Granth Sahib.The goal of Sikhism is to be one with God.[72] Sikhs meditate as a means to progress towards enlightenment; it is devoted meditation simran that enables a sort of communication between the Infinite and finite human consciousness.[73] There is no concentration on the breath but chiefly the remembrance of God through the recitation of the name of God[74] and surrender themselves to Gods presence often metaphorized as surrendering themselves to the Lord's feet.[75]

East-Asian mysticsm[edit]

Taoism[edit]

Main article: Taoism

Taoist philosophy is centered on the Tao, usually translated "Way", an ineffable cosmic principle. The contrasting yet interdependent concepts of yin and yang also symbolise harmony, with Taoist scriptures often emphasing the Yin virtues of femininity, passivity and yieldingness.[76] Taoist practice includes exercises and rituals aimed at manipulating the life force Qi, and obtaining health and longevity.[note 9] These have been elaborated into practices such as Tai chi, which are well known in the west.Western esotericism[edit]

Main article: Western esotericism

The Fourth Way[edit]

The Fourth Way is a term used by George Gurdjieff to describe an approach to self-development he learned over years of travel in the East[77] that combined what he saw as three established traditional "ways," or "schools" into a fourth way,[78] namely the schools of the body, the mind and the emotions. The Fourth Way emphasizes that people live their lives in a state of "waking sleep", but that higher levels of consciousness and various inner abilities are possible.[79] The Fourth Way teaches people how to increase and focus their attention and energy in various ways, and to minimize daydreaming and absentmindedness.[80][81] The Fourth Way is an "in the world" practice, which rejects retreats and other forms of seclusion. Its central concentrative technique, self remembering, is to be practised, as far as possible, under all circumstances. According to fourth way teaching, inner development in oneself is the beginning of a possible further process of change, whose aim is to transform a man into what Gurdjieff taught he ought to be.[82]Mysticism and morality[edit]

A philosophical issue in the study of mysticism is the relation of mysticism to morality. Albert Schweitzer presented the classic account of mysticism and morality being incompatible.[83] Arthur Danto also argued that morality is at least incompatible with Indian mystical beliefs.[84] Walter Stace, on the other hand, argued not only are mysticism and morality compatible, but that mysticism is the source and justification of morality.[85] Others studying multiple mystical traditions have concluded that the relation of mysticism and morality is not as simple as that.[86]Richard King also points to disjunction between "mystical experience" and social justice:[87]

The privatisation of mysticism – that is, the increasing tendency to locate the mystical in the psychological realm of personal experiences – serves to exclude it from political issues as social justice. Mysticism thus becomes seen as a personal matter of cultivating inner states of tranquility and equanimity, which, rather than seeking to transform the world, serve to accommodate the individual to the status quo through the alleviation of anxiety and stress.[87]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- Jump up ^ Original quote in "Evelyn Underhill (1930), Mysticism: A Study in the Nature and Development of Spiritual Consciousness.[7]

- Jump up ^ Underhill: "One of the most abused words in the English language, it has been used in different and often mutually exclusive senses by religion, poetry, and philosophy: has been claimed as an excuse for every kind of occultism, for dilute transcendentalism, vapid symbolism, religious or aesthetic sentimentality, and bad metaphysics. on the other hand, it has been freely employed as a term of contempt by those who have criticized these things. It is much to be hoped that it may be restored sooner or later to its old meaning, as the science or art of the spiritual life."[7]

- Jump up ^ According to Waaijman, the traditional meaning of spirituality is a process of re-formation which "aims to recover the original shape of man, the image of God. To accomplish this, the re-formation is oriented at a mold, which represents the original shape: in Judaism the Torah, in Christianity Christ, in Buddhism Buddha, in the Islam Muhammad."[10] Waaijman uses the word "omvorming",[10] "to change the form". Different translations are possible: transformation, re-formation, trans-mutation. Waaijman points out that "spirituality" is only one term of a range of words which denote the praxis of spirituality.[11] Some other terms are "Hasidism, contemplation, kabbala, asceticism, mysticism, perfection, devotion and piety".[11]

- Jump up ^ Compare the use of the terms bodhi, kensho and satori in Buddhism, commonly translated as "enlightenment", and vipassana, which all point to cognitive processes of intuition and comprehension, in contrast to the mind-calming techniques of samatha and samadhi.

- Jump up ^ According to Evelyn Underhill, illumination is a generic English term for the phenomenon of mysticism. The term illumination is derived from the Latin illuminatio, applied to Christian prayer in the 15th century. Translated as enlightenment it is adopted in English translations of Buddhist texts, but used loosely to describe the state of mystical attainment regardless of faith.[16][a]

- Jump up ^ The term "mystical experience" has become synonymous with the terms "religious experience", spiritual experience and sacred experience.[18]

- Jump up ^ According to W.F. Cobb, mysticism is the pursuit of communion with, identity with, or conscious awareness of an ultimate reality, divinity, spiritual truth, or God through direct experience, intuition, instinct or insight. Mysticism usually centers on practices intended to nurture those experiences.[24] According to Cobb, mysticism may be dualistic, maintaining a distinction between the self and the divine, or may be nondualistic.[24]

- Jump up ^ blakemore and Jennett add: "[T]he common assumption that all mystical experiences, whatever their context, are the same cannot, of course, be demonstrated." They also state: "Some have placed a particular emphasis on certain altered states, such as visions, trances, levitations, locutions, raptures, and ecstasies, many of which are altered bodily states. Margery Kempe's tears and Teresa of Avila's ecstasies are famous examples of such mystical phenomena. But many mystics have insisted that while these experiences may be a part of the mystical state, they are not the essence of mystical experience, and some, such as Origen, Meister Eckhart, and John of the Cross, have been hostile to such psycho-physical phenomena. Rather, the essence of the mystical experience is the encounter between God and the human being, the Creator and creature; this is a union which leads the human being to an ‘absorption’ or loss of individual personality. It is a movement of the heart, as the individual seeks to surrender itself to ultimate Reality; it is thus about being rather than knowing. For some mystics, such as Teresa of Avila, phenomena such as visions, locutions, raptures, and so forth are by-products of, or accessories to, the full mystical experience, which the soul may not yet be strong enough to receive. Hence these altered states are seen to occur in those at an early stage in their spiritual lives, although ultimately only those who are called to achieve full union with God will do so."[web 4]

- Jump up ^ Extending to physical immortality: the Taoist pantheon includes Xian, or immortals.

- Jump up ^ According to Wright, the use of the western word enlightenment is based on the supposed resemblance of bodhi with Aufklärung, the independent use of reason to gain insight into the true nature of our world. As a matter of fact there are more resemblances with Romanticism than with the Enlightenment: the emphasis on feeling, on intuitive insight, on a true essence beyond the world of appearances.[17] See also Enlightenment (spiritual).

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g King 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b King 2002, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Horne 1996, p. 9.

- Jump up ^ Paden 2009, p. 332.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McMahan 2008, p. 269, note 9.

- Jump up ^ Parsoon 2011, p. 3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Underhill 2012, p. xiv.

- Jump up ^ Bloom 2010, p. 12.

- Jump up ^ Parson 2011, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Waaijman 2000, p. 460.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Waaijman 2002, p. 315.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McGinn 2006.

- Jump up ^ Moores 2005, p. 34.

- Jump up ^ Belzen 2003, p. 7.

- Jump up ^ Lidke 2005, p. 144.

- Jump up ^ Evelyn Underhill. Practical Mysticism. Wilder Publications, new edition 2008. ISBN 978-1-60459-508-6

- Jump up ^ Wright 2000, pp. 181–183.

- Jump up ^ Samy 1998, p. 80.

- Jump up ^ Hori 1999, p. 47.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sharf 2000.

- Jump up ^ Harmless 2007, pp. 10–17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b James 1982 (1902), p. 30.

- Jump up ^ Harmless 2007, p. 14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cobb 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Parsons 2011, p. 3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b King 2002, p. 195.

- Jump up ^ King 2002, pp. 16–18.

- Jump up ^ King 2002, p. 16.

- Jump up ^ King 2002, pp. 16–17.

- Jump up ^ King 2002, p. 17.

- Jump up ^ Hanegraaff 1996.

- ^ Jump up to: a b King 2002.

- Jump up ^ McMahan 2010.

- Jump up ^ Parson 2011, p. 3-5.

- Jump up ^ Harmless 2007, p. 3.

- Jump up ^ Parsons 2011, pp. 3–4.

- Jump up ^ McMahan 2010, p. 269, note 9.

- Jump up ^ Sharf 1995-B.

- Jump up ^ Katz 2000, p. 3.

- Jump up ^ Katz 2000, pp. 3–4.

- Jump up ^ Kerényi, Karoly, "Kore," in C.G. Jung and C. Kerényi, Essays on a Science of Mythology: The Myth of the Divine Child and the Mysteries of Eleusis. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963: pages 101–55.

- Jump up ^ Eliade, Mircea, A History of Religious Ideas: From the Stone Age to the Eleusinian Mysteries. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978.

- Jump up ^ "Imbued with Holiness" – The relationship of the esoteric to the exoteric in the fourfold Pardes interpretation of Torah and existence. From www.kabbalaonline.org

- Jump up ^ Alan Godlas, University of Georgia, Sufism's Many Paths, 2000, University of Georgia

- Jump up ^ Nuh Ha Mim Keller, "How would you respond to the claim that Sufism is Bid'a?", 1995. Fatwa accessible at: Masud.co.uk

- Jump up ^ Zubair Fattani, "The meaning of Tasawwuf", Islamic Academy. Islamicacademy.org

- Jump up ^ Ahmed Zarruq, Zaineb Istrabadi, Hamza Yusuf Hanson—"The Principles of Sufism". Amal Press. 2008.

- Jump up ^ Seyyedeh Dr. Nahid Angha. "origin of the Wrod Tasawouf". Ias.org. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- Jump up ^ Xinjiang Sufi Shrines

- Jump up ^ Dumoulin 2005-A.

- Jump up ^ Dumoulin 2005-B.

- Jump up ^ D.T. Suzuki. Mysticism: Christian and Buddhist. Routledge, 2002. ISBN 978-0-415-28586-5

- Jump up ^ Raju 1992.

- Jump up ^ White 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b King 2001.

- Jump up ^ Bryant 2009, p. 10, 457.

- Jump up ^ Denise Lardner Carmody, John Carmody, Serene Compassion. Oxford University Press US, 1996, page 68.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stuart Ray Sarbacker, Samādhi: The Numinous and Cessative in Indo-Tibetan Yoga. SUNY Press, 2005, pp. 1–2.

- Jump up ^ Tattvarthasutra [6.1], see Manu Doshi (2007) Translation of Tattvarthasutra, Ahmedabad: Shrut Ratnakar p. 102

- Jump up ^ Bryant 2009, p. 10.

- Jump up ^ Raju 1992, p. 177.

- Jump up ^ Sivananda 1993, p. 217.

- Jump up ^ King 1999.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nicholson 2010.

- Jump up ^ Einoo, Shingo (ed.) (2009). Genesis and Development of Tantrism. University of Tokyo. p. 45.

- Jump up ^ White 2000, p. 7.

- Jump up ^ Harper (2002), p. 2.

- Jump up ^ Nikhilanada (1982), pp. 145–160

- Jump up ^ Harper (2002), p. 3.

- Jump up ^ Kalra, Surjit (2004). Stories Of Guru Nanak. Pitambar Publishing. ISBN 9788120912755.

- Jump up ^ Lebron, Robyn (2012). Searching for Spiritual Unity...can There be Common Ground?: A Basic Internet Guide to Forty World Religions & Spiritual Practices. CrossBooks. p. 399. ISBN 9781462712618.

- Jump up ^ Sri Guru Granth Sahib. p. Ang 12.

- Jump up ^ "The Sikh Review" 57 (7-12). Sikh Cultural Centre. 2009: 35.

- Jump up ^ Sri Guru Granth Sahib. p. Ang 1085.

- Jump up ^ Sri Guru Granth Sahib. p. Ang 1237.

- Jump up ^ Mysticism: A guide for the Perplexed. Oliver, P.

- Jump up ^ P.D. Ouspensky (1949), In Search of the Miraculous, Chapter 2

- Jump up ^ P.D. Ouspensky (1949), In Search of the Miraculous, Chapter 15

- Jump up ^ G. I. Gurdjieff and His School by Jacob Needleman Professor of Philosophy

- Jump up ^ G.I. Gurdjieff (first privately printed in 1974). Life is Real Only Then, When 'I Am'

- Jump up ^ Olga de Hartmann (1973). Views from the Real World, Energy and Sleep

- Jump up ^ G.I. Gurdjieff (1950). Beelzebub's Tales to His Grandson

- Jump up ^ Schweitzer 1936

- Jump up ^ Danto 1987

- Jump up ^ Stace 1960, pp. 323-343.

- Jump up ^ Barnard and Kripal 2002; Jones 2004.

- ^ Jump up to: a b King 2002, p. 21.

Sources[edit]

Published sources[edit]

- Barnard, William G. and Jeffrey J. Kripal, eds. (2002), Crossing Boundaries: Essays on the Ethical Status of Mysticism, Seven Bridges Press

- Beauregard, Mario and Denyse O'Leary (2007), The Spiritual Brain, Seven Bridges Press

- Bhattacharya, Vidhushekhara (1943), Gauḍapādakārikā, New York: HarperCollins

- Belzen, Jacob A.; Geels, Antoon (2003), Mysticism: A Variety of Psychological Perspectives, Rodopi

- Bloom, Harold (2010), Aldous Huxley, Infobase Publishing

- Bryant, Ernest J. (1953), Genius and Epilepsy. Brief sketches of Great Men Who Had Both, Concord, Massachusetts: Ye Old Depot Press

- Bryant, Edwin (2009), The Yoga Sutras of Patañjali: A New Edition, Translation, and Commentary, New York, USA: North Point Press, ISBN 978-0865477360

- Carrithers, Michael (1983), The Forest Monks of Sri Lanka

- Cobb, W.F. (2009), Mysticism and the Creed, BiblioBazaar, ISBN 978-1-113-20937-5

- Comans, Michael (2000), The Method of Early Advaita Vedānta: A Study of Gauḍapāda, Śaṅkara, Sureśvara, and Padmapāda, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Danto, Arthur C. (1987), Mysticism and Morality, New York: Columbia University Press

- Dasgupta, Surendranath (1975), A History of Indian Philosophy 1, Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0412-0

- Day, Matthew (2009), Exotic experience and ordinary life. In: Micael Stausberg (ed.)(2009), "Contemporary Theories of Religion", pp. 115–129, Routledge

- Devinsky, O. (2003), "Religious experiences and epilepsy", Epilepsy & Behavior 4 (2003) 76–77

- Dewhurst, K.; Beard, A. (2003). "Sudden religious conversions in temporal lobe epilepsy. 1970." (PDF). Epilepsy & Behaviour 4 (1): 78–87. doi:10.1016/S1525-5050(02)00688-1. PMID 12609232.

- Drvinsky, Julie; Schachter, Steven (2009), "Norman Geschwind's contribution to the understanding of behavioral changes in temporal lobe epilepsy: The February 1974 lecture", Epilepsy & Behavior 15 (2009) 417-424

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005-A), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 1: India and China, World Wisdom Books, ISBN 978-0-941532-89-1 Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005-B), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 2: Japan, World Wisdom Books, ISBN 978-0-941532-90-7 Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Evans, Donald. (1989), Can Philosophers Limit What Mystics Can Do?, Religious Studies, volume 25, pp. 53-60

- Forman, Robert K., ed. (1997), The Problem of Pure Consciousness: Mysticism and Philosophy, Oxford University Press

- Forman, Robert K. (1999), Mysticism, Albany: State University of New York Press

- Geschwind, Markus; Picard, Fabienne (2014), "Ecstatic Epileptic Seizures – the Role of the Insula in Altered Self-Awareness" (PDF), Epileptologie 2014; 31: 87 – 98

- Hakuin, Ekaku (2010), Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin, Translated by Norman Waddell, Shambhala Publications

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (1996), New Age Religion and Western Culture. Esotericism in the mirror of Secular Thought, Leiden/New York/Koln: E.J. Brill

- Harmless, William (2007), Mystics, Oxford University Press

- Harper, Katherine Anne (ed.); Robert L. Brown (ed.) (2002), The Roots of Tantra, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-5306-5 Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - Hisamatsu, Shinʼichi (2002), Critical Sermons of the Zen Tradition: Hisamatsu's Talks on Linji, University of Hawaii Press

- Holmes, Ernest (2010), The Science of Mind: Complete and Unabridged, Wilder Publications, ISBN 1604599898

- Horne, James R. (1996), mysticism and Vocation, Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press

- Hood, Ralph W. (2003), Mysticism. In: Hood e.a., "The Psychology of Religion. An Empirical Approach", pp 290–340, New York: The Guilford Press

- Hori, Victor Sogen (1994), Teaching and Learning in the Zen Rinzai Monastery. In: Journal of Japanese Studies, Vol.20, No. 1, (Winter, 1994), 5–35 (PDF)

- Hori, Victor Sogen (1999), Translating the Zen Phrase Book. In: Nanzan Bulletin 23 (1999) (PDF)

- Hori, Victor Sogen (2006), The Steps of Koan Practice. In: John Daido Loori,Thomas Yuho Kirchner (eds), Sitting With Koans: Essential Writings on Zen Koan Introspection, Wisdom Publications

- Hügel, Friedrich, Freiherr von (1908), The Mystical Element of Religion: As Studied in Saint Catherine of Genoa and Her Friends, London: J.M. Dent

- Jacobs, Alan (2004), Advaita and Western Neo-Advaita. In: The Mountain Path Journal, autumn 2004, pages 81–88, Ramanasramam

- James, William (1982) [1902], The Varieties of Religious Experience, Penguin classics

- Jones, Richard H. (1983), Mysticism Examined, Albany: State University of New York Press

- Jones, Richard H. (2004), Mysticism and Morality, Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books

- Kapleau, Philip (1989), The Three Pillars of Zen, ISBN 978-0-385-26093-0

- Katz, Steven T. (2000), Mysticism and Sacred Scripture, Oxford University Press

- Kim, Hee-Jin (2007), Dōgen on Meditation and Thinking: A Reflection on His View of Zen, SUNY Press

- King, Richard (1999), Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East", Routledge

- King, Richard (2002), Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East", Routledge

- King, Sallie B. (1988), Two Epistemological Models for the Interpretation of Mysticism, Journal for the American Academy for Religion, volume 26, pp. 257-279

- Klein, Anne Carolyn; Tenzin Wangyal (2006), Unbounded Wholeness : Dzogchen, Bon, and the Logic of the Nonconceptual: Dzogchen, Bon, and the Logic of the Nonconceptual, Oxford University Press

- Klein, Anne Carolyn (2011), Dzogchen. In: Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass (eds.)(2011), The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy, Oxford University Press

- Kraft, Kenneth (1997), Eloquent Zen: Daitō and Early Japanese Zen, University of Hawaii Press

- Leuba, J.H. (1925), The psychology of religious mysticism, Harcourt, Brace

- Lewis, James R.; Melton, J. Gordon (1992), Perspectives on the New Age, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-1213-X

- Lidke, Jeffrey S. (2005), Interpreting across Mystical Boundaries: An Analysis of Samadhi in the Trika-Kaula Tradition. In: Jacobson (2005), "Theory And Practice of Yoga: Essays in Honour of Gerald James Larson", pp 143–180, BRILL

- Low, Albert (2006), Hakuin on Kensho. The Four Ways of Knowing, Boston & London: Shambhala

- MacInnes, Elaine (2007), The Flowing Bridge: Guidance on Beginning Zen Koans, Wisdom Publications

- Maezumi, Taizan; Glassman, Bernie (2007), The Hazy Moon of Enlightenment, Wisdom Publications

- McGinn, Bernard (2006), The Essential Writings of Christian Mysticism, New York: Modern Library

- McMahan, David L. (2008), The Making of Buddhist Modernism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195183276

- Mohr, Michel (2000), Emerging from Nonduality. Koan Practice in the Rinzai Tradition since Hakuin. In: steven Heine & Dale S. Wright (eds.)(2000), "The Koan. texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism", Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Moores, D.J. (2006), Mystical Discourse in Wordsworth and Whitman: A Transatlantic Bridge, Peeters Publishers

- Mumon, Yamada (2004), Lectures On The Ten Oxherding Pictures, University of Hawaii Press

- Nakamura, Hajime (2004), A History of Early Vedanta Philosophy. Part Two, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited

- Newberg, Andrew; d'Aquili, Eugene (2008), Why God Won't Go Away: Brain Science and the Biology of Belief, Random House LLC

- Newberg, Andrew and Mark Robert Waldman (2009), How God Changes Your Brain, New York: Ballantine Books

- Nicholson, Andrew J. (2010), Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History, Columbia University Press

- Paden, William E. (2009), Comparative religion. In: John Hinnells (ed.)(2009), "The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion", pp. 225–241, Routledge

- Parsons, William B. (2011), Teaching Mysticism, Oxford University Press

- Picard, Fabienne (2013), "State of belief, subjective certainty and bliss as a product of cortical dysfuntion", Cortex 49 (2013) pp.2494-2500

- Picard, Fabienne; Kurth, Florian (2014), "Ictal alterations of consciousness during ecstatic seizures", Epilepsy & Behavior 30 (2014) 58-61

- Presinger, Michael A. (1987), Neuropsychological Bases of God Beliefs, New York: Praeger

- Proudfoot, Wayne (1985), Religious Experiences, Berkeley: University of California Press

- Puligandla, Ramakrishna (1997), Fundamentals of Indian Philosophy, New York: D.K. Printworld (P) Ltd.

- Raju, P.T. (1992), The Philosophical Traditions of India, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited

- Rambachan, Anatanand (1994), The Limits of Scripture: Vivekananda's Reinterpretation of the Vedas, University of Hawaii Press

- Renard, Philip (2010), Non-Dualisme. De directe bevrijdingsweg, Cothen: Uitgeverij Juwelenschip

- Samy, AMA (1998), Waarom kwam Bodhidharma naar het Westen? De ontmoeting van Zen met het Westen, Asoka: Asoka

- Sawyer, Dana (2012), Afterword: The Man Who Took Religion Seriously: Huston Smith in Context. In: Jefferey Pane (ed.)(2012), "The Huston Smith Reader: Edited, with an Introduction, by Jeffery Paine", pp 237–246, University of California Press

- Schopenhauer, Arthur (1844), Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung 2

- Sekida, Katsuki (1985), Zen Training. Methods and Philosophy, New York, Tokyo: Weatherhill

- Sharf, Robert H. (1995-B), "Buddhist Modernism and the Rhetoric of Meditative Experience" (PDF), NUMEN, vol.42 (1995) Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Sharf, Robert H. (2000), The Rhetoric of Experience and the Study of Religion. In: Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7, No. 11-12, 2000, pp. 267–87 (PDF)

- Sivananda, Swami (1993), All About Hinduism, The Divine Life Society

- Snelling, John (1987), The Buddhist handbook. A Complete Guide to Buddhist Teaching and Practice, London: Century Paperbacks

- Spilka e.a. (2003), The Psychology of Religion. An Empirical Approach, New York: The Guilford Press

- Stace, W.T. (1960), Mysticism and Philosophy, London: Macmillan

- Schweitzer, Albert (1938), Indian Thought and its Development, New York: Henry Holt

- Takahashi, Shinkichi (2000), Triumph of the Sparrow: Zen Poems of Shinkichi Takahashi, Grove Press

- Taves, Ann (2009), Religious Experience Reconsidered, Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Underhill, Evelyn (2012), Mysticism: A Study in the Nature and Development of Spiritual Consciousness, Courier Dover Publications

- Waaijman, Kees (2000), Spiritualiteit. Vormen, grondslagen, methoden, Kampen/Gent: Kok/Carmelitana

- Waaijman, Kees (2002), Spirituality: Forms, Foundations, Methods, Peeters Publishers

- Waddell, Norman (2010), Foreword to "Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin", Shambhala Publications

- Wainwright, William J. (1981), Mysticism, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press

- White, David Gordon (ed.) (2000), Tantra in Practice, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-05779-6

- White, David Gordon (2012), The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India, University of Chicago Press

- Wilber, Ken (1996), The Atman Project: A Transpersonal View of Human Development, Quest Books

- Wright, Dale S. (2000), Philosophical Meditations on Zen Buddhism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Om, Swami (2014), If Truth Be Told: A Monk's Memoir, Harper Collins

Web-sources[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j "Gellman, Jerome, "Mysticism", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)". Plato.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Dan Merkur, Mysticism, Encyclopedia Britannica

- Jump up ^ James McClenon, Mysticism, Encyclopedia of Religion and Society

- ^ Jump up to: a b Colin Blakemore and Shelia Jennett (2001), The Oxford Companion to the Body

Further reading[edit]

- Baba, Meher (1995). Discourses. Myrtle Beach, S.C.: Sheriar Foundation.

- Bailey, Raymond. Thomas Merton On Mysticism. DoubleDay, New York. 1975.

- Daniels, P., Horan A. Mystic Places. Alexandria, Time-Life Books, 1987.

- Dasgupta, S. N. Hindu Mysticism. New York: F. Ungar Publishing Co., 1927, "republished 1959". xx, 168 p.

- Dinzelbacher, Peter. Mystik und Natur. Zur Geschichte ihres Verhältnisses vom Altertum bis zur Gegenwart. (Theophrastus Paracelsus Studien, 1) Berlin, 2009.

- Elior, Rachel, Jewish Mysticism: The Infinite Expression of Freedom, Oxford. Portland, Oregon: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2007.

- Fanning, Steven., Mystics of the Christian Tradition. New York: Routledge Press, 2001.

- Jacobsen, Knut A. (Editor); Larson, Gerald James (Editor) (2005). Theory And Practice of Yoga: Essays in Honour of Gerald James Larson. Brill Academic Publishers (Studies in the History of Religions, 110). Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - Harmless, William, Mystics. Oxford, 2008.

- Harvey, Andrew. The Essential Gay Mystic. HarperSanFrancisco-Harper Collins Publishers. 1997.

- King, Ursula. Christian Mystics: Their Lives and Legacies Throughout the Ages. London: Routledge 2004.

- Kroll, Jerome, Bernard Bachrach. The Mystic Mind: The Psychology of Medieval Mystics and Ascetics. New York and London: Routledge, 2005.

- Langer, Otto. Christliche Mystik im Mittelalter. Mystik und Rationalisierung – Stationen eines Konflikts. Darmstadt, 2004.

- Louth, Andrew., The Origins of the Christian Mystical Tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Masson, Jeffrey and Terri C. Masson. Buried Memories on the Acropolis. Freud's Relation to Mysticism and Anti-Semitism. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, Volume 59, 1978, pages 199–208.

- McColman, Carl. The Big Book of Christian Mysticism. Hampton Roads Publishing Company, Inc. 2010.

- McKnight, C.J. Mysticism, the Experience of the Divine: Medieval Wisdom. Chronicle Books, 2004.

- McGinn, Bernard, The Presence of God: A History of Western Christian Mysticism'.' Volumes 1 – 4. (The Foundations of Mysticism; The Growth of Mysticism; The Flowering of Mysticism) New York, Crossroad, 1997–2005.

- Merton, Thomas, An Introduction to Christian Mysticism: Initiation into the Monastic Tradition, 3. Kalamazoo, 2008.

- Nelstrop, Louise, Kevin Magill and Bradley B. Onishi, Christian Mysticism: An Introduction to Contemporary Theoretical Approaches. Aldershot, 2009.

- Otto, Rudolf (author); Bracy, Bertha L. (translator) & Payne, Richenda C. 1932, 1960. Mysticism East and West: A Comparative Analysis of the Nature of Mysticism. New York, N. Y., USA: The Macmillan Company

- Stace, W. T. Mysticism and Philosophy. 1960.

- Stace, W. T. The Teachings of the Mystics, 1960.

- Underhill, Evelyn. Mysticism: A Study in the Nature and Development of Spiritual Consciousness. 1911

- Stark, Ryan J. "Some Aspects of Christian Mystical Rhetoric, Philosophy, and Poetry," Philosophy and Rhetoric 41 (2008): 260–77.

- Wilber, Ken (2000), Sex, Ecology, Spirituality, Shambhala Publications

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mysticism |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mysticism. |

- Encyclopedia Britannica, Mysticism

- Jerome Gellmann, Mysticism, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- James McClenon, Mysticism, Encyclopedia of Religion and Society

- Encyclopedia.com, Mysticism

- Resources – Medieval Jewish History – Jewish Mysticism The Jewish History Resource Center, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Shaku soens influence on western notions of mysticism

- "Self-transcendence enhanced by removal of portions of the parietal-occipital cortex" Article from the Institute for the Biocultural Study of Religion

| ||

| ||

| ||

|

No comments:

Post a Comment