From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Alistair Hardy)

| Sir Alister C. Hardy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 10, 1896 |

| Died | May 22, 1985 (aged 89) |

| Nationality | English |

| Fields | Marine Zoology |

Contents[hide] |

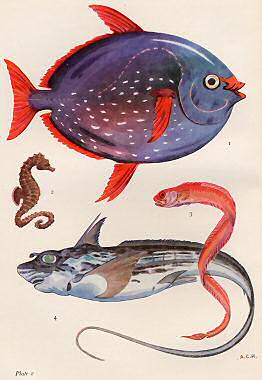

[edit] Camoufleur and artist

Hardy's artistry in the service of science:

Rare and Unusual Fish in British Waters.

1. Opah, Lampris guttatus.

2. Sea Horse, Hippocampus europaeus.

3. Red Bandfish, Cepola rubescens.

4. Rabbit-fish, Chimaera monstrosa

Rare and Unusual Fish in British Waters.

1. Opah, Lampris guttatus.

2. Sea Horse, Hippocampus europaeus.

3. Red Bandfish, Cepola rubescens.

4. Rabbit-fish, Chimaera monstrosa

He was selected for camouflage work by the artist Solomon J. Solomon, who apparently mistook him for a different Hardy who was a professional artist.[3] Hardy had sufficient artistic skill to serve his scientific work. He illustrated his New Naturalist books with his own line drawings, maps, diagrams, photographs, and paintings.[4] For example, plate 2 of Fish and Fisheries illustrates the depicted "Rare and Unusual Fish in British Waters" both accurately and vividly. Hardy described the camoufleurs as including artists and "scientists with artistic inclinations", himself perhaps among them.[3]equally drawn to science and art, and if the truth be known, I must confess that it is the latter that has the greater appeal. I am lucky in not having been torn between the two; I have managed to combine them.[2]

In later life, Hardy travelled in India, Sri Lanka, Burma, Cambodia, China and Japan, recording his visits to temples in all those countries in watercolour paintings. Many of these are in the University of Wales Trinity Saint David collection.[5]

[edit] Biology and zoology

Hardy was the first Professor of Zoology at the University of Hull from 1928 - 1942. In 1942, he was then appointed Professor of Natural History at the University of Aberdeen, where he remained until 1946, when he became Linacre Professor of Zoology in Oxford, a position he held until 1961. In 1940, Hardy was made a Fellow of the Royal Society.[1] He was knighted in 1957.

[edit] Evolution

Hardy discussed his evolutionary ideas in his book The Living Stream (1965), he had written a chapter titled "Biology and Telepathy" in the book where he explained that "something akin to telepathy might possibly influence the process of evolution". His views on evolution has been described by some as vitalist.[6] Hardy also suggested that certain animals share a "group mind" which he described as "a sort of psychic blueprint between members of a species." He also speculated that all species might be linked in a "cosmic mind" capable of carrying evolutionary information through space and time.[7][edit] Aquatic ape hypothesis

In 1930, while reading Wood Jones' Man's Place among the Mammals, which included the question of why humans, unlike all other land mammals, had fat attached to their skin, Hardy realized that this trait sounded like the blubber of marine mammals, and began to suspect that humans had ancestors that were more aquatic than previously imagined. Fearing the backlash of such a radically different idea, he kept this hypothesis secret until 1960, when he spoke, and later wrote, on the subject, which subsequently became known as the aquatic ape hypothesis in academic circles.[edit] Study of religion

Dating from his boyhood at Oundle School, Hardy had a lifelong interest in spiritual phenomena, but aware that his interests were likely to be considered unorthodox in the scientific community, apart from occasional lectures he kept his opinions to himself until his retirement from his Oxford Chair. During the academic sessions of 1963-4 and 1964-5, he gave the Gifford Lectures at Aberdeen University on the evolution of religion, later published as The Living Stream and The Divine Flame. These lectures signalled his wholehearted return to his religious interests. In 1969 he founded the Religious Experience Research Unit in Manchester College, Oxford. The Unit began its work by compiling a database of religious experiences and continues to investigate the nature and function of spiritual and religious experience at the University of Wales, Lampeter.Hardy's biological approach to the roots of religion is currently shared by a number of other researchers (cf. Scott Atran, Pascal Boyer) but unlike them Hardy did not wish to be reductionist, seeing religious awareness as having evolved in response to a genuine dimension of reality. For his work in founding the Religious Experience Research Centre, Hardy received the Templeton Prize shortly before his death in 1985.[8]

[edit] Works

Hardy wrote numerous scientific papers on plankton, fish and whales. He wrote two popular books in the New Naturalist series, and in later life he also wrote on religion.- Books

- The Open Sea. Its Natural History (Part I) The World of Plankton. New Naturalist #34, Collins, 1956.

- The Open Sea. Its Natural History (Part II) Fish & Fisheries. New Naturalist #37, Collins, 1959.

- The Living Stream: A Restatement of Evolution Theory and its Relationship to the Spirit of Man. Harper and Row, 1965.

- Papers

- The Herring in Relation to its Animate Environment. Fish. Invest. Lond., II, 7:3. 1951.

- (with E.R. Gunther) The Plankton of the South Georgia Whaling Grounds and Adjacent Waters, 1926-7. 'Discovery' Report, II, 1-146.

[edit] Recognition

Hardy's "pioneering work" was recognised by South Georgia & South Sandwich Islands in 2011 with a set of four commemorative stamps bearing his image.[9][edit] References

- ^ a b Marshall, N. B. (1986). "Alister Clavering Hardy. 10 February 1896-22 May 1985". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society 32: 222–226. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1986.0008.

- ^ a b Behrens, Roy R (February 2009). "Revisiting Abbott Thayer: non-scientific reflections about camouflage in art, war and zoology". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364 (1516): 497-501. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0250. http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/364/1516/497.full.

- ^ a b Forbes, Peter. Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage. Yale, 2009. Page 101.

- ^ Hardy, The Open Sea, 1956 and 1959.

- ^ Schmidt, Bettina (2012). "Sir Alister Hardy's Art". The Alister Hardy Society. http://alisterhardysociety.weebly.com/hardys-art.html. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ Ernst Mayr Toward a new philosophy of biology: observations of an evolutionist 1988, p. 13

- ^ Sylvia Fraser A Book of Strange 1993, p. 60

- ^ Hardy's contribution to the scientific study of religion is reviewed in David Hay's book Something There: The Biology of the Human Spirit published in London in July 2006 by Darton, Longman & Todd and in the United States by Templeton Press in 2007.

- ^ Stamps Issues: SGSSI Recognize the Pioneering Work of Sir Alister Hardy . 19 March 2011.

[edit] Further reading

- David Hay, God’s Biologist: A life of Alister Hardy (London, Darton Longman and Todd, 2011).

[edit] External links

- Alister Hardy Society Homepage

- Archives Hub

- Australian Continuous Plankton Recorder Project

- Sir Alister Hardy Foundation for Ocean Science (SAHFOS)

| ||

| ||

| ||

No comments:

Post a Comment