From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Blogger Reference Link http://www.p2pfoundation.net/Multi-Dimensional_Science| It has been suggested that astrologer be merged into this article or section. (Discuss) Proposed since August 2012. |

Not to be confused with Astronomy.

| Astrology | |||||||||||

| The astrological signs | |||||||||||

| Aries • Taurus • Gemini • Cancer • Leo • Virgo • Libra Scorpio • Sagittarius • Capricorn • Aquarius • Pisces | |||||||||||

| Categories of astrology content | |||||||||||

| —————— Expand list for reference —————— | |||||||||||

| Quick links: branches | |||||||||||

| Chinese • Decumbiture • Electional • Esoteric • Financial • Hellenistic • Horary • Locational • Mundane • Psychological • Meteorological • Uranian • Vedic | |||||||||||

| The planets in astrology | |||||||||||

| Sun • Moon • Mercury • Mars • Jupiter • Saturn • Uranus • Pluto | |||||||||||

| Astrology portal | Astrology project | ||||||||||

| Astrologers • Astrological organizations Astrological traditions, types, and systems | |||||||||||

Among Indo-European peoples, astrology has been dated to the third millennium BCE, with roots in calendrical systems used to predict seasonal shifts and to interpret celestial cycles as signs of divine communications.[1] Through most of its history, astrology was considered a scholarly tradition. It was accepted in political and academic contexts, and was connected with other studies, such as astronomy, alchemy, meteorology, and medicine.[2] At the end of the 17th century, new scientific concepts in astronomy (such as heliocentrism) called astrology into question, and subsequent controlled studies failed to confirm its predictive value. Astrology thus lost its academic and theoretical standing.

Astrology is a pseudoscience, and as such is rejected by the academic and scientific communities. Some scientific testing of astrology has been conducted, and no evidence has been found to support any of the premises or purported effects outlined in astrological traditions. Furthermore, there is no proposed mechanism of action by which the positions and motions of stars and planets could affect people and events on Earth that does not contradict well understood, basic aspects of biology and physics.[3]:249[4]

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Etymology

The word astrology comes from the early Latin word astrologia,[5] deriving from the Greek noun ἀστρολογία, 'account of the stars'. Astrologia later passed into meaning 'star-divination' with astronomia used for the scientific term.[6][edit] Principles and practice

Although most cultural systems of astrology share common roots in ancient philosophies that influenced each other, many have unique methodologies which differ from those developed in the West. These include Hindu astrology (also known as "Indian astrology" and in modern times referred to as "Vedic astrology") and Chinese astrology, both of which have influenced the world's cultural history.

[edit] Western

For more details on this topic, see Western astrology.

Western astrology is a form of divination based on the construction of a horoscope for an exact moment, such as a person's birth.[9] It uses the tropical zodiac, which is aligned to the equinoctial points.[10]Western astrology is founded on the movements and relative positions of celestial bodies such as the Sun, Moon, planets, which are analyzed by their movement through signs of the zodiac (spatial divisions of the ecliptic) and by their aspects (angles) relative to one another. They are also considered by their placement in houses (spatial divisions of the sky).[11] Astrology's modern representation in western popular media is usually reduced to sun sign astrology, which considers only the zodiac sign of the Sun at an individual's date of birth, and represents only 1/12 of the total chart.[12] The names of the zodiac correspond to the names of the constellations originally within the respective segment and are in Latin.[citation needed]

Along with tarot divination, astrology is one of the core studies of Western esotericism, and as such has influenced systems of magical belief not only among Western esotericists and Hermeticists, but also belief systems such as Wicca that have borrowed from or been influenced by the Western esoteric tradition. Tanya Luhrmann has said that "all magicians know something about astrology," and refers to a table of correspondences in Starhawk's The Spiral Dance, organized by planet, as an example of the astrological lore studied by magicians.[13]

[edit] Indian and South Asian

For more details on this topic, see Hindu astrology.

Hindu astrology originated with western astrology.[14]:361 In the earliest Indian astronomy texts, the year was believed to be 360 days long, similar to that of Babylonian astrology, but the rest of the early astrological system bears little resemblance.[15]:229 Later, the Indian techniques were augmented with some of the Babylonian techniques.[15]:231 Hindu astrology is oriented toward predicting one's fate or destiny.[16]:237[unreliable source?] Hindu astrology relies on the sidereal zodiac in which the signs of the zodiac are aligned to the position of the corresponding constellations in the sky. In order to maintain this alignment, Hindu astrology uses an adjustment, called ayanamsa, to take into account the gradual precession of the vernal equinox (the gradual shift in the orientation of the Earth's axis of rotation). In Hindu astrology the equinox occurs when the Sun is 6 degrees in Pisces. Western astrology places the equinox at the beginning of Aries, about 23 degrees after the equinox in the Hindu system.[16][unreliable source?] Hindu astrology also includes several sub-systems of zodiac division, and employs the notion of bandhu: connections that, according to the Vedas link the outer and the inner worlds.[citation needed]Sri Lankan astrology is largely based on Hindu astrology with some modifications to bring it in line with Buddhist teachings. Tibetan astrology also shares many of these components but has also been strongly influenced by Chinese culture and acknowledges a circle of animal signs similar to that of the Chinese zodiac (see below).[citation needed]

[edit] Chinese and East-Asian

For more details on this topic, see Chinese astrology and Chinese zodiac.

Chinese astrology has a close relation with Chinese philosophy (theory of the three harmonies: heaven, earth and man) and uses concepts such as yin and yang, the Five phases, the 10 Celestial stems, the 12 Earthly Branches, and shichen (時辰 a form of timekeeping used for religious purposes). The early use of Chinese astrology was mainly confined to political astrology, the observation of unusual phenomena, identification of portents and the selection of auspicious days for events and decisions.[17]:22,85,176The constellations of the Zodiac of western Asia and Europe were not used; instead the sky is divided into Three Enclosures (三垣 sān yuán), and Twenty-eight Mansions (二十八宿 èrshíbā xiù) in twelve Ci (十二次).[18] The Chinese zodiac of twelve animal signs is said to represent twelve different types of personality. It is based on cycles of years, lunar months, and two-hour periods of the day (the shichen). The zodiac traditionally begins with the sign of the Rat, and the cycle proceeds through 11 other animals signs: the Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Goat, Monkey, Rooster, Dog and Pig.[19] Complex systems of predicting fate and destiny based on one's birthday, birth season, and birth hours, such as ziping and Zi Wei Dou Shu (simplified Chinese: 紫微斗数; traditional Chinese: 紫微斗數; pinyin: zǐwēidǒushù) are still used regularly in modern day Chinese astrology. They do not rely on direct observations of the stars.[20]

The Korean zodiac is identical to the Chinese one. The Vietnamese zodiac is almost identical to Chinese zodiac except that the second animal is the Water Buffalo instead of the Ox, and the fourth animal is the Cat instead of the Rabbit. The Japanese zodiac includes the Wild Boar instead of the Pig. The Thai zodiac includes a Naga in place of the Dragon and begins, not at Chinese New Year, but at either on the first day of fifth month in Thai lunar calendar, or during the Songkran festival (now celebrated every 13–15 April), depending on the purpose of the use.[21]

[edit] History

Main article: History of astrology

[edit] Ancient world

For more details on ancient astrology, see Babylonian astrology and Hellenistic astrology.

Astrology, in its broadest sense, is the search for meaning in the sky. It has therefore been argued that astrology began as a study as soon as human beings made conscious attempts to measure, record, and predict seasonal changes by reference to astronomical cycles.[22]:2,3 Early evidence of such practices appears as markings on bones and cave walls, which show that lunar cycles were being noted as early as 25,000 years ago; the first step towards recording the Moon’s influence upon tides and rivers, and towards organizing a communal calendar.[23]:81ff Agricultural needs were also met by increasing knowledge of constellations, whose appearances change with the seasons, allowing the rising of particular star-groups to herald annual floods or seasonal activities.[24][verification needed] By the third millennium BCE, widespread civilizations had developed sophisticated awareness of celestial cycles, and are believed to have consciously oriented their temples to create alignment with the heliacal risings of the stars.[25]There is scattered evidence to suggest that the oldest known astrological references are copies of texts made during this period. Two, from the Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa (compiled in Babylon around 1700 BCE) are reported to have been made during the reign of king Sargon of Akkad (2334–2279 BCE).[26] Another, showing an early use of electional astrology, is ascribed to the reign of the Sumerian ruler Gudea of Lagash (ca. 2144–2124 BCE). This describes how the gods revealed to him in a dream the constellations that would be most favorable for the planned construction of a temple.[27] However, there is controversy about whether they were genuinely recorded at the time or merely ascribed to ancient rulers by posterity. The oldest undisputed evidence of the use of astrology as an integrated system of knowledge is therefore attributed to the records of the first dynasty of Mesopotamia (1950–1651 BCE).

The system of Chinese astrology was elaborated during the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BC) and flourished during the Han Dynasty (2nd century BC to 2nd century AD), during which all the familiar elements of traditional Chinese culture – the Yin-Yang philosophy, theory of the 5 elements, Heaven and Earth, Confucian morality – were brought together to formalise the philosophical principles of Chinese medicine and divination, astrology and alchemy.[17]:3,4

[edit] Medieval Islamic world

For more details on this topic, see Astrology in medieval Islam.

Latin translation of Abū Maʿshar's De Magnis Coniunctionibus (‘Of the great conjunctions’), Venice, 1515.

Other important Arabic astrologers include Albumasur and Al Khwarizmi, the Persian mathematician, astronomer and astrologer, who is considered the father of algebra and the algorithm. The Arabs greatly increased the knowledge of astronomical cycles, and many of the star names that remain in common use today, such as Aldebaran, Altair, Betelgeuse, Rigel and Vega retain the legacy of their language.

[edit] Since 1900

| This section requires expansion. (September 2012) |

Early in the twentieth century psychologist Carl Jung developed some concepts concerning astrology,[30] which led to the development of psychological astrology.[29]:251-256[31][32]

Other new developments included Uranian astrology,[33] Astrocartography[34][35] and Financial astrology.

[edit] Cultural influence

Main article: Cultural influence of astrology

In the West there have been occasional reports of political leaders consulting astrologers. Louis de Wohl worked as an astrologer for the British intelligence agency MI5, after it was claimed that Hitler used astrology to time his actions. The War Office was "interested to know what Hitler's own astrologers would be telling him from week to week".[36] In fact de Wohl's predictions were so inaccurate that he was soon labelled a "complete charlatan" and it was later shown that Hitler considered astrology to be "complete nonsense".[37] After John Hinckley's attempted assassination of U.S. President Ronald Reagan, first lady Nancy Reagan commissioned astrologer Joan Quigley to act as the secret White House astrologer. However, Quigley's role ended in 1988 when it became public through the memoirs of former chief of staff, Donald Regan.[38]In India, there is a long-established and widespread belief in astrology. It is commonly used for daily life, particularly in matters concerning marriage and career, and makes extensive use of electional, horary and karmic astrology.[39][40] Indian politics has also been influenced by astrology.[41] It remains considered a branch of the Vedanga.[42][43] In 2001, Indian scientists and politicians debated and critiqued a proposal to use state money to fund research into astrology,[44] resulting in permission for Indian universities to offer courses in Vedic astrology.[45] In February 2011, the Bombay High Court reaffirmed astrology's standing in India when it dismissed a case which had challenged its status as a science.[46]

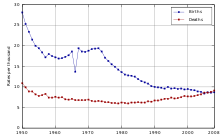

In Japan, a strong belief in astrology has led to dramatic changes in the fertility rate and the number of abortions in the years of "Fire Horse". Women born in these years are called hinoeuma, and believed to be unmarriageable and to bring bad luck to their father or husband. In 1966, the number of babies born in Japan dropped by over 25% as parents tried to avoid the stigma of having a daughter born in the hinoeuma year.[47][48]

[edit] Scientific appraisal

Astrology is a pseudoscience[49][50]:1350 that has not demonstrated its effectiveness in controlled studies and has no scientific validity.[51][52]:85 The majority of professional astrologers rely on performing astrology-based personality tests and making relevant predictions about the remunerators future.[52]:83 Those who continue to have faith in astrology have been characterized as doing so "in spite of the fact that there is no verified scientific basis for their beliefs, and indeed that there is strong evidence to the contrary."[53] Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson commented on astrological belief, noting that "part of knowing how to think is knowing how the laws of nature shape the world around us. Without that knowledge, without that capacity to think, you can easily become a victim of people who seek to take advantage of you".[54]The former astrologer, and scientist, Geoffrey Deans and psychologist Ivan Kelly[55] conducted a large scale scientific test, involving more than one hundred cognitive, behavioral, physical and other variables, but found no support for astrology.[56] Furthermore, a meta-analysis was conducted pooling 40 studies consisting of 700 astrologers and over 1000 birth charts. Ten of the tests, which had a total of 300 participants, involved subjects picking the correct chart interpretation out of a number of others which were not the astrologically correct chart interpretation (usually 3 to 5 others). When the date and other obvious clues were removed no significant results were found to suggest there was any preferred chart.[56]:190 A further test involved 45 confident[a] astrologers, with an average of 10 years experience and 160 participants (out of an original sample size of 1198 participants) who strongly favoured certain characteristics in the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire to extremes.[56]:191 The astrologers performed much worse than merely basing decisions off the individuals age, and much worse than 45 control subjects who didn't use birth charts at all.[b][56]:191

Science and non-science are often distinguished by the criterion of falsifiability. The criterion was first proposed by philosopher of science Karl Popper. To Popper, science does not rely on induction, instead scientific investigations are inherently attempts to falsify existing theories through novel tests. If a single test fails, then the theory is falsified. Therefore, any test of a scientific theory must prohibit certain results which will falsify the theory, and expect other specific results which will be consistent with the theory. Using this criterion of falsifiability, astrology is a pseudoscience.[57] Popper regarded astrology as "pseudo-empirical" in that "it appeals to observation and experiment", but "nevertheless does not come up to scientific standards".[58]:44

In 1953, sociologist Theodor W. Adorno conducted a study of the astrology column of a Los Angeles newspaper as part of a project examining mass culture in capitalist society. Adorno concluded that astrology was a large-scale manifestation of systematic irrationalism, where individuals were subtly being led to believe that the author of the column was addressing them directly through the use of flattery and vague generalizations.[59]

[edit] Cognitive bias

See also: Forer effect

It has also been suggested that much of the continued faith in astrology could be psychologically explained as a matter of cognitive bias.[60]:42-48 In 1949 Bertram Forer conducted a personality test on students.[61] While seemingly giving the students individualized results, he instead gave each student exactly the same sheet that discussed their personality. The personality descriptions were taken from a book on Astrology. When the students were asked to comment on the accuracy of the test with a rating more than 40% gave it the top mark of 5 out of 5, and the average rating was 4.2.[62]:134, 135 The results of this study have been replicated in numerous other studies.[63]:382 Thus, study of this Barnum/Forer effect has been mostly focused on the level of acceptance of fake horoscopes and fake astrological personality profiles.[63]:382 Recipients of these personality assessments consistently fail to distinguish common and uncommon personality descriptors.[63]:383By a process known as self-attribution, it has been shown in numerous studies that individuals with knowledge of astrology tend to describe their personality in terms of traits compatible with their star sign. The effect is heightened when the individuals were aware the personality description was being used to discuss astrology. Individuals who were not familiar with astrology had no such tendency.[64]

[edit] Lack of consistency

Testing the validity of astrology can be hard because there is no consensus amongst astrologers as to what astrology is or what it can predict.[52]:83 Most professional astrologers are paid to predict the future or describe a person's personality and life, but most horoscopes only make vague untestable statements that can almost apply to any individual.[52]:83 Astrologers avoid making verifiable predictions and instead rely on making vague statements which allows them to try to avoid falsification.[58]:48-49Georges Charpak and Henri Broch dealt with claims from astrology in the book Debunked! ESP, Telekinesis, and other Pseudoscience.[65] They pointed out that astrologers have only a small knowledge of astronomy and that they often do not take into account basic features such as the precession of the equinoxes which would change the position of the sun with time; they commented on the example of Elizabeth Teissier who claimed that "the sun ends up in the same place in the sky on the same date each year" as the basis for claims that two people with the same birthday but a number of years apart should be under the same planetary influence. Charpak and Broch noted that "there is a difference of about twenty-two thousand miles between Earth's location on any specific date in two successive years" and that thus they should not be under the same influence according to astrology. Over a 40 years period there would be a difference greater than 780,000 miles.[66]

The tropical zodiac has no connection to the stars and avoids the issue with precession moving the constellations as long as they make no reference to the constellations themselves being in the associated zodiacal sign.[66] Charpak and Broch, noting this, referred to astrology based on the tropical zodiac as being "empty boxes that have nothing to do with anything and are devoid of any consistency or correspondence with the stars".[66] Sole usage of the tropical zodiac is inconsistent with references made, by the same astrologers, to the Age of Aquarius which is dependent on when the vernal point enters the constellation of Aquarius.[51]

Some astrologers make claims that the position of all the planets must be taken into account, but astrologers were unable to predict the existence of Neptune based on mistakes in horoscopes. Instead Neptune was predicted using Newton's law of universal gravitation.[52] The grafting on of Uranus, Neptune and Pluto into the astrology discourse was done on an ad-hoc basis.[51]

On the demotion of Pluto to the status of dwarf planet, Philip Zarka of the Paris Observatory in Meudon, France wondered how astrologers should respond:[51]

- "Should astrologers remove it from the list of luminars [Sun, Moon and the 8 planets other than earth] and confess that it did not actually bring any improvement? If they decide to keep it, what about the growing list of other recently discovered similar bodies (Sedna, Quaoar. etc), some of which even have satellites (Xena, 2003EL61)?"

[edit] Lack of mechanism

Astrology has been criticized for failing to provide a physical mechanism that links the movements of celestial bodies to their purported effects on human behaviour. In a lecture in 2001, Stephen Hawking stated "The reason most scientists don't believe in astrology is because it is not consistent with our theories that have been tested by experiment."[67] In 1975, amid increasing popular interest in astrology, The Humanist magazine presented a rebuttal of astrology in a statement put together by Bart J. Bok, Lawrence E. Jerome, and Paul Kurtz.[53] The statement, entitled ‘Objections to Astrology’, was signed by 186 astronomers, physicists and leading scientists of the day. They said that there is no scientific foundation for the tenets of astrology and warned the public against accepting astrological advice without question. Their criticism focused on the fact that there was no mechanism whereby astrological effects might occur:Astronomer Carl Sagan declined to sign the statement. Sagan said he took this stance not because he thought astrology had any validity, but because he thought that the tone of the statement was authoritarian, and that dismissing astrology because there was no mechanism (while "certainly a relevant point") was not in itself convincing. In a letter published in a follow-up edition of The Humanist, Sagan confirmed that he would have been willing to sign such a statement had it described and refuted the principal tenets of astrological belief. This, he argued, would have been more persuasive and would have produced less controversy.[69]

Many astrologers claim that astrology is scientific.[70] Some of these astrologers have proposed conventional causal agents such as electromagnetism and gravity.[70][71] Scientists dismiss these mechanisms as implausible[70] since, for example, the magnetic field, when measured from earth, of a large but distant planet such as Jupiter is far smaller than that produced by ordinary household appliances.[71] Other astrologers prefer not to attempt to explain astrology,[72][dubious ] and instead give it supernatural explanations such as divination.[73]:xxii Carl Jung sought to invoke synchronicity to explain results on astrology from a single study he conducted, where no statistically significant results were observed. Sychronicity itself is considered to be neither testable nor falsifiable.[74] The study was subsequently heavily criticised for its non-random sample and its use of statistics and also its lack of consistency with astrology.[c][75]

[edit] Carlson's experiment

Across several centuries of testing, the predictions of astrology have never been more accurate than that expected by chance alone.[52] One approach used in testing astrology quantitatively is through blind experiment. When specific predictions from astrologers were tested in rigorous experimental procedures in the Carlson test, the predictions were falsified.[51] The Shawn Carlson's double-blind chart matching tests, in which 28 astrologers agreed to match over 100 natal charts to psychological profiles generated by the California Psychological Inventory (CPI) test, is one of the most renowned tests of astrology.[76] The experimental protocol used in Carlson's study was agreed to by a group of physicists and astrologers prior to the actual experiment itself.[51] Astrologers, nominated by the National Council for Geocosmic Research, acted as the astrological advisors, and helped to ensure that the test was fair. They also choose 26 of the 28 astrologers for the tests (the other 2 being interested astrologers) themselves.[77]:420 The astrologers helped to draw up the central proposition of natal astrology to be tested.[77]:419 Published in Nature in 1985, the study found that predictions based on natal astrology were no better than chance, and that the testing "clearly refutes the astrological hypothesis".[77][edit] Gauquelin's research

Main article: Mars effect

The initial Mars effect finding, showing the relative frequency of the diurnal position of Mars in the birth charts (N = 570) of "eminent athletes" (red solid line) compared to the expected results [after Michel Gauquelin 1955][78]

[edit] Theological criticisms

Some of the practices of astrology were contested on theological grounds by medieval Muslim astronomers such as Al-Farabi (Alpharabius), Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) and Avicenna. They said that the methods of astrologers conflicted with orthodox religious views of Islamic scholars through the suggestion that the Will of God can be known and predicted in advance.[81]For example, Avicenna’s 'Refutation against astrology' Risāla fī ibṭāl aḥkām al-nojūm, argues against the practice of astrology while supporting the principle of planets acting as the agents of divine causation which express God's absolute power over creation. Avicenna considered that the movement of the planets influenced life on earth in a deterministic way, but argued against the capability of determining the exact influence of the stars.[82] In essence, Avicenna did not refute the essential dogma of astrology, but denied our ability to understand it to the extent that precise and fatalistic predictions could be made from it.[83]

Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya (1292–1350), in his Miftah Dar al-SaCadah, also used physical arguments in astronomy to question the practice of judicial astrology.[84] He recognized that the stars are much larger than the planets, and argued:[85]

Belief in astrology is incompatible with Catholic beliefs[86] such as free will.[87] According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church:"And if you astrologers answer that it is precisely because of this distance and smallness that their influences are negligible, then why is it that you claim a great influence for the smallest heavenly body, Mercury? Why is it that you have given an influence to al-Ra's and al-Dhanab, which are two imaginary points [ascending and descending nodes]?"—Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya

St. Augustine believed that astrology conflicted with church doctrine, but he grounded his opposition with non-theological reasons such as the failure of astrology to explain twins who behave differently although are conceived at the same moment and born at approximately the same time.[87]All forms of divination are to be rejected: recourse to Satan or demons, conjuring up the dead or other practices falsely supposed to "unveil" the future. Consulting horoscopes, astrology, palm reading, interpretation of omens and lots, the phenomena of clairvoyance, and recourse to mediums all conceal a desire for power over time, history, and, in the last analysis, other human beings, as well as a wish to conciliate hidden powers. They contradict the honor, respect, and loving fear that we owe to God alone.[88]—Catechism of the Catholic Church

[edit] See also

[edit] Notes

- ^ The level of confidence was self rated by the astrologers themselves.

- ^ Also discussed in Martens, Ronny; Trachet, Tim (1998). Making sense of astrology. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. ISBN 1573922188.

- ^ Jung made the claims, despite being aware that there was no statistical significance in the results. Looking for coincidences post hoc is of very dubious value, see Misuse_of_statistics#Data_dredging.[74]

[edit] References

- ^ Koch-Westenholz, Ulla (1995). Mesopotamian astrology : an introduction to Babylonian and Assyrian celestial divination. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. Foreword,11. ISBN 978-87-7289-287-0.

- ^ Kassell, Lauren (5 May 2010). "Stars, spirits, signs: towards a history of astrology 1100–1800". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 41 (2): 67–69. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2010.04.001.

- ^ Vishveshwara, edited by S.K. Biswas, D.C.V. Mallik, C.V. (1989). Cosmic perspectives : essays dedicated to the memory of M.K.V. Bappu (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521343542.

- ^ Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association, vol. 1. Dordrecht u.a.: Reidel u.a.. 1978. ISBN 978-0-917586-05-7. http://www.cavehill.uwi.edu/bnccde/PH29A/thagard.html.

- "Chapter 7: Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Understanding". science and engineering indicators 2006. National Science Foundation. http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind06/c7/c7s2.htm#c7s2l3. Retrieved 28 July 2012. "About three-fourths of Americans hold at least one pseudoscientific belief; i.e., they believed in at least 1 of the 10 survey items[29]" ..." Those 10 items were extrasensory perception (ESP), that houses can be haunted, ghosts/that spirits of dead people can come back in certain places/situations, telepathy/communication between minds without using traditional senses, clairvoyance/the power of the mind to know the past and predict the future, astrology/that the position of the stars and planets can affect people's lives, that people can communicate mentally with someone who has died, witches, reincarnation/the rebirth of the soul in a new body after death, and channeling/allowing a "spirit-being" to temporarily assume control of a body."

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "astrology". Online Etymology Dictionary. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=astrology. Retrieved 2011-12-06. "Differentiation between astrology and astronomy began late 1400s and by 17c. this word was limited to "reading influences of the stars and their effects on human destiny.""

- ^ "astrology, n.". Oxford English Dictionary (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989; online version September 2011. http://www.oed.com/viewdictionaryentry/Entry/12267. "In Old French and Middle English astronomie seems to be the earlier and general word, astrologie having been subseq. introduced for the ‘art’ or practical application of astronomy to mundane affairs, and thus gradually limited by 17th cent. to the reputed influences of the stars, unknown to science. Not in Shakespeare."

- ^ The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica,' v.5, 1974, p. 916

- ^ Dietrich, Thomas: 'The Origin of Culture and Civilization, Phenix & Phenix Literary Publicists, 2005, p. 305

- ^ Dictionary of the history of ideas. New York: Scribner. 1974. ISBN 0-684-13293-1. http://xtf.lib.virginia.edu/xtf/view?docId=DicHist/uvaBook/tei/DicHist1.xml;brand=default;.

- ^ James R. Lewis, 2003. The Astrology Book: the Encyclopedia of Heavenly Influences. Visible Ink Press. Online at Google Books.

- ^ Hone, Margaret (1978). The Modern Text-Book of Astrology. Romford, U.K.: L. N. Fowler & Co. Ltd.. pp. 21-89. ISBN 0852433573.

- ^ Riske, Kris (2007). Llewellyn's Complete Book of Astrology. Minnesota, USA: Llewellyn Publications. pp. 5-6; 27. ISBN 978-0-7387-1071-6.

- ^ Luhrmann, Tanya (1991). Persuasions of the witch's craft: ritual magic in contemporary England. Harvard University Press. pp. 147–151. ISBN 0-674-66324-1.

- ^ Pingree, David (18). "Indian Astronomy". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. American Philosophical Society 122 (6): 361-364. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/986451. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ a b Pingree, David (June 1963). "Astronomy and Astrology in India and Iran". Isis. The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society 54 (2): 229-246. http://www.jstor.org/stable/228540.

- ^ a b Braha, James (1995). How to predict your future : secrets of eastern & western astrology[unreliable source?]. Hollywood, FL: Hermetician Press. ISBN 9780935895070.

- ^ a b The Chinese sky during the Han : constellating stars and society. Leiden: Brill. 1997. ISBN 978-90-04-10737-3.

- ^ F. Richard Stephenson, "Chinese Roots of Modern Astronomy", New Scientist, 26 June 1980. See also 二十八宿的形成与演变

- ^ Theodora Lau, The Handbook of Chinese Horoscopes, pp2-8, 30–5, 60–4, 88–94, 118–24, 148–53, 178–84, 208–13, 238–44, 270–78, 306–12, 338–44, Souvenir Press, New York, 2005

- ^ Selin, Helaine, ed. (1997). "Astrology in China". Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer. http://books.google.bg/books?id=raKRY3KQspsC&pg=PA76&dq=astrology+in+China+Springer&hl=en&sa=X&ei=7NILUNvWDeeq0AWD1djHCg&sqi=2&ved=0CCsQ6AEwAA. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- ^ "การเปลี่ยนวันใหม่ การนับวัน ทางโหราศาสตร์ไทย การเปลี่ยนปีนักษัตร โหราศาสตร์ ดูดวง ทำนายทายทัก". http://www.myhora.com/%E0%B8%AA%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%9E%E0%B8%B1%E0%B8%99%E0%B9%82%E0%B8%AB%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%A8%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%AA%E0%B8%95%E0%B8%A3%E0%B9%8C/%E0%B8%81%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%B1%E0%B8%9A%E0%B8%A7%E0%B8%B1%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%97%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%87%E0%B9%82%E0%B8%AB%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%A8%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%AA%E0%B8%95%E0%B8%A3%E0%B9%8C-004.aspx.

- ^ Campion, Nicholas (2009). History of western astrology. Volume II, The medieval and modern worlds. (1. publ. ed.). London [u.a.]: Continuum.. ISBN 978-1-4411-8129-9.

- ^ Marshack, Alexander (1991). The roots of civilization : the cognitive beginnings of man's first art, symbol and notation (Rev. and expanded. ed.). Mount Kisco, N.Y.: Moyer Bell. ISBN 978-1-55921-041-6.

- ^ Evelyn-White, Hesiod ; with an English translation by Hugh G. (1977). The Homeric hymns and Homerica (Reprinted. ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. pp. 663-677. ISBN 978-0-674-99063-0. ""Fifty days after the solstice, when the season of wearisome heat is come to an end, is the right time to go sailing. Then you will not wreck your ship, nor will the sea destroy the sailors, unless Poseidon the Earth-Shaker be set upon it, or Zeus, the king of the deathless gods""

- ^ Aveni, David H. Kelley, Eugene F. Milone ; foreword by Anthony F. (2005). Exploring ancient skies an encyclopedic survey of archaeoastronomy (Online-Ausg. ed.). New York: Springer. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-387-95310-6.

- ^ Two texts which refer to the 'omens of Sargon' are reported in E. F. Weidner, ‘Historiches Material in der Babyonischen Omina-Literatur’ Altorientalische Studien, ed. Bruno Meissner, (Leipzig, 1928-9), v. 231 and 236.

- ^ From scroll A of the ruler Gudea of Lagash, I 17 – VI 13. O. Kaiser, Texte aus der Umwelt des Alten Testaments, Bd. 2, 1–3. Gütersloh, 1986–1991. Also quoted in A. Falkenstein, ‘Wahrsagung in der sumerischen Überlieferung’, La divination en Mésopotamie ancienne et dans les régions voisines. Paris, 1966.

- ^ Bīrūnī, Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad (1879.). "VIII". The chronology of ancient nations. London, Pub. for the Oriental translations fund of Great Britain & Ireland by W. H. Allen and co.. LCCN 01006783.

- ^ a b c Campion, Nicholas (2009). History of western astrology. Volume II, The medieval and modern worlds. (1. publ. ed.). London [u.a.]: Continuum.. ISBN 9781441181299. "“At the same time, in Switzerland, the psychologist Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) was developing sophisticated theories concerning astrology...”"

- ^ selected, C.G. Jung ;; Hull, edited by Gerhard Adler, in collaboration with Aniela Jaffé ; translations from the German by R.F.C. (19uu). C.G. Jung Letters : 1906-1950.. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09895-1. "Letter from Jung to Freud, 12 June 1911 “I made horoscopic calculations in order to find a clue to the core of psychological truth.”"

- ^ Gieser, Suzanne. The Innermost Kernel, Depth Psychology and Quantum Physics. Wolfgang Pauli’s Dialogue with C.G.Jung, (Springer, Berlin, 2005) p. 21 ISBN 3-540-20856-9

- ^ Campion, Nicholas. "Prophecy, Cosmology and the New Age Movement. The Extent and Nature of Contemporary Belief in Astrology."( Bath Spa University College, 2003) via Campion, Nicholas, History of Western Astrology, (Continuum Books, London & New York, 2009) pp. 248, 256, ISBN 978-1-84725-224-1

- ^ Harding, M & Harvey, C, Working with Astrology, The Psychology of Midpoints, Harmonics and Astro*Carto*Graphy, (Penguin Arkana 1990) (3rd edition pp. 8–13) ISBN 1-873948-03-4

- ^ Davis, Martin, From Here to There, An Astrologer’s Guide to Astromapping, (Wessex Astrologer, England, 2008) Ch1. History, p. 2, ISBN 978-1-902405-27-8

- ^ Lewis, Jim & Irving, Ken, The Psychology of Astro*Carto*Graphy, (Penguin Arkana 1997) ISBN 1-357-91864-2

- ^ "The Strange Story Of Britain's "State Seer"". The Sydney Morning Herald. August 30, 1952. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=JrdVAAAAIBAJ&sjid=5bADAAAAIBAJ&pg=6779,6948658&dq=hitler-astrologer&hl=en. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ "Star turn: astrologer who became SOE's secret weapon against Hitler". The Guardian. March 4, 2008. http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2008/mar/04/nationalarchives.secondworldwar. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ Regan, Donald T. (1988). For the record : from Wall Street to Washington (1st ed. ed.). San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-163966-3.

- Quigley, Joan (1990). What does Joan say? : my seven years as White House astrologer to Nancy and Ronald Reagan. Secaucus, NJ: Birch Lane Press. ISBN 1-55972-032-8.

- "The Reagan Chart Watch; Astrologer Joan Quigley, Eye on the Cosmos". The Washington Post (The Washington Post). http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/washingtonpost/access/73606295.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&date=May+11%2C+1988&author=Cynthia+Gorney&pub=The+Washington+Post+%28pre-1997+Fulltext%29&edition=&startpage=c.01&desc=The+Reagan+Chart+Watch%3B+Astrologer+Joan+Quigley%2C+Eye+on+the+Cosmos. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ Kaufman, Michael T. (23 December 1998). "BV Raman Dies". New York Times, 23 December 1998. http://www.nytimes.com/1998/12/23/world/bangalore-venkata-raman-indian-astrologer-dies-at-86.html. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- ^ Dipankar Das, May 1996. "Fame and Fortune". http://www.lifepositive.com/mind/predictive-sciences/astrology.asp. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- ^ "Soothsayers offer heavenly help". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/428081.stm. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ "In countries such as India, where only a small intellectual elite has been trained in Western physics, astrology manages to retain here and there its position among the sciences." David Pingree and Robert Gilbert, "Astrology; Astrology In India; Astrology in modern times". Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008

- ^ Mohan Rao, Female foeticide: where do we go? Indian Journal of Medical Ethics Oct-Dec2001-9(4)[1]

- ^ "Indian Astrology vs Indian Science". BBC. 31 May 2001. http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/sci_tech/highlights/010531_vedic.shtml.

- ^ "Guidelines for Setting up Departments of Vedic Astrology in Universities Under the Purview of University Grants Commission". Government of India, Department of Education. Archived from the original on 2011-05-12. http://web.archive.org/web/20110512154221/http://www.education.nic.in/circulars/astrologycurriculum.htm. Retrieved 26 March 2011. "There is an urgent need to rejuvenate the science of Vedic Astrology in India, to allow this scientific knowledge to reach to the society at large and to provide opportunities to get this important science even exported to the world,"

- ^ 'Astrology is a science: Bombay HC', The Times of India, 3 February 2011

- ^ "Japanese childrearing: two generations of scholarship". 1996. http://books.google.com/books?id=1bTGN21ev2MC&pg=PA22&dq=hinoeuma&hl=en&sa=X&ei=66cLUMDsPMuxrAfBso3ICA&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAQ. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- ^ "The Political Economy of Japan: Cultural and social dynamics". 1992. http://books.google.com/books?id=uAOrAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA22&dq=hinoeuma&hl=en&sa=X&ei=66cLUMDsPMuxrAfBso3ICA&ved=0CD0Q6AEwAw. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- ^ "Science and Pseudo-Science". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pseudo-science/. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- "Astronomical Pseudo-Science: A Skeptic's Resource List". Astronomical Society of the Pacific. http://www.astrosociety.org/education/resources/pseudobib.html.

- ^ Hartmann, P; Reuter M, Nyborga H (May 2006). "The relationship between date of birth and individual differences in personality and general intelligence: A large-scale study". Personality and Individual Differences 40 (7): 1349–1362. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.017. "To optimise the chances of finding even remote relationships between date of birth and individual differences in personality and intelligence we further applied two different strategies. The first one was based on the common chronological concept of time (e.g. month of birth and season of birth). The second strategy was based on the (pseudo-scientific) concept of astrology (e.g. Sun Signs, The Elements, and astrological gender), as discussed in the book ‘‘Astrology: Science or superstition?’’ by Eysenck and Nias (1982)."

- ^ a b c d e f Zarka, Philippe (2011). "Astronomy and astrology". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union 5 (S260): 420–425. doi:10.1017/S1743921311002602.

- ^ a b c d e f The cosmic perspective (4th ed. ed.). San Francisco, Calif.: Pearson/Addison-Wesley. 2007. pp. 82–84. ISBN 0805392831.

- ^ a b c "Objections to Astrology: A Statement by 186 Leading Scientists". The Humanist, September/October 1975. Archived from the original on 18 March 2009. http://web.archive.org/web/20090318140638/http://www.americanhumanist.org/about/astrology.html.

- ^ "Ariz. Astrology School Accredited". The Washington Post. 27 August 2001. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/aponline/20010827/aponline135357_000.htm.

- ^ Matthews, Robert (17 Aug 2003). "Astrologers fail to predict proof they are wrong". The Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1439101/Astrologers-fail-to-predict-proof-they-are-wrong.html. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d Dean G, Kelly I.W. (2003). "Is Astrology Relevant to Consciousness and Psi?". Journal of Consciousness Studies 10 (6-7): 175-198.

- ^ Stephen Thornton, Edward N. Zalta (older edition). "Karl Popper". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/popper/.

- ^ a b Popper, Karl (2004). Conjectures and refutations : the growth of scientific knowledge (Reprinted. ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28594-1.

- The relevant piece is also published in, Schick Jr, Theodore, (2000). Readings in the philosophy of science : from positivism to postmodernism. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Pub. pp. 33-39. ISBN 0767402774.

- ^ Theodor W. Adorno (Spring 1974). "The Stars Down to Earth: The Los Angeles Times Astrology Column". Telos 1974 (19): 13-90. doi:10.3817/0374019013. http://journal.telospress.com/content/1974/19/13.short.

- ^ Eysenck, H.J.; Nias, D.K.B. (1984). Astrology : science or superstition?. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-022397-5.

- ^ Forer, Bertram R. (1 January 1949). "The fallacy of personal validation: a classroom demonstration of gullibility.". The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 44 (1): 118–123. doi:10.1037/h0059240.

- ^ Paul, Annie Murphy (2005). The cult of personality testing : how personality tests are leading us to miseducate our children, mismanage our companies, and misunderstand ourselves. (1st pbk. ed. ed.). New York, N.Y.: Free Press. ISBN 0743280725.

- ^ a b c Rogers, P.; Soule, J. (5 March 2009). "Cross-Cultural Differences in the Acceptance of Barnum Profiles Supposedly Derived From Western Versus Chinese Astrology". Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 40 (3): 381–399. doi:10.1177/0022022109332843.

- ^ Wunder, Edgar (1 December 2003). "Self-attribution, sun-sign traits, and the alleged role of favourableness as a moderator variable: long-term effect or artefact?". Personality and Individual Differences 35 (8): 1783–1789. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00002-3. "The effect was replicated several times (Eysenck & Nias 1981,1982; Fichten & Sunerton, 1983; Jackson, 1979; Kelly, 1982; Smithers & Cooper, 1978), even if no reference to astrology was made until the debriefing of the subjects (Hamilton, 1995; Van Rooij, 1994, 1999), or if the data were gathered originally for a purpose which has nothing to do with astrology at all (Clarke, Gabriels, & Barnes, 1996; Van Rooij, Brak, & Commandeur, 1988), but the effect is stronger when a cue is given to the subjects that the study is about astrology (Van Rooij 1994). Early evidence for sun-sign derived self-attribution effects has already been reported by Silverman (1971) and Delaney & Woodyard (1974). In studies with subjects unfamiliar with the meaning of the astrological sun-sign symbolism, no effect was observed (Fourie, 1984; Jackson & Fiebert, 1980; Kanekar & Mukherjee, 1972; Mohan, Bhandari, & Meena, 1982; Mohan and Gulati, 1986; Saklofske, Kelly, & McKerracher, 1982; Silverman & Whitmer, 1974; Veno & Pamment, 1979)."

- ^ Giomataris, Ioannis. "Nature Obituary Georges Charpak (1924–2010)". Nature. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v467/n7319/full/4671048a.html. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ^ a b c Charpak, Georges; Holland, Henri Broch ; translated by Bart K. (2004). Debunked! : ESP, telekinesis, and other pseudoscience. Baltimore [u.a.9: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press. p. 6,7. ISBN 0801878675. http://books.google.ie/books?id=DpnWcMzeh8oC&q=astrology#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ "British Physicist Debunks Astrology in Indian Lecture". Associated Press. http://www.beliefnet.com/story/63/story_6346_1.html.

- ^ Bok, Bart J.; Lawrence E. Jerome, Paul Kurtz (1982). "Objections to Astrology: A Statement by 186 Leading Scientists". In Patrick Grim. Philosophy of Science and the Occult. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 14–18. ISBN 0-87395-572-2.

- ^ The Humanist, volume 36, no.5 (1976).

- ^ a b c Chris, French. "Astrologers and other inhabitants of parallel universes". 7 February 2012. The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2012/feb/07/astrologers-parallel-universes. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ a b Randi, James. "UK MEDIA NONSENSE — AGAIN". 21 May 2004. Swift, Online newspaper of the JREF. http://www.randi.org/jr/052104uk.html. Retrieved 8 July 2012.[dead link]

- ^ M. Harding. "Prejudice in Astrological Research". Correlation, Vol 19(1). http://www.astrozero.co.uk/astroscience/harding.htm.

- ^ Curry, Geoffrey Cornelius ; foreword by Patrick (2003). The moment of astrology : origins in divination (Rev. and expanded 2nd ed. ed.). Bournemouth: Wessex Astrologer. ISBN 1-902405-11-0. ""despite all appearances of objectivity and natural law. It is divination despite the fact that aspects of symbolism can be approached through scientific method, and despite the possibility that some factors in horoscopy can arguably be validated by the appeal to science.""

- ^ a b editor, Michael Shermer, (2002). The Skeptic encyclopedia of pseudoscience.. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 241. ISBN 1576076539.

- ^ Samuels, Andrew (1990). Jung and the post-Jungians. London: Tavistock/Routledge. p. 80. ISBN 0203359291.

- ^ Muller, Richard (2010). "Web site of Richard A. Muller, Professor in the Department of Physics at the University of California at Berkeley,". http://muller.lbl.gov/homepage.html. Retrieved 2011-08-02.My former student Shawn Carlson published in Nature magazine the definitive scientific test of Astrology.

Maddox, Sir John (1995). "John Maddox, editor of the science journal Nature, commenting on Carlson's test". http://www.randi.org/encyclopedia/astrology.html. Retrieved 2011-08-02. " ... a perfectly convincing and lasting demonstration." - ^ a b c Carlson, Shawn (1985). "A double-blind test of astrology". Nature 318 (6045): 419–425. Bibcode 1985Natur.318..419C. doi:10.1038/318419a0. http://muller.lbl.gov/papers/Astrology-Carlson.pdf.

- ^ a b Gauquelin, Michel (1955). L'influence des astres : étude critique et expérimentale. Paris: Éditions du Dauphin.

- ^ Gauquelin, Michel (Fall 1988). "Is There Really a Mars Effect?". Above & Below Journal of Astrological Studies (11): 4–7. http://www.theoryofastrology.com/gauquelin/mars_effect.htm.

- ^ Benski, Claude, et al., The "Mars Effect" (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1996).

- ^ Saliba, George (1994b). A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam. New York University Press. pp. 60 & 67–69. ISBN 0-8147-8023-7.

- ^ Catarina Belo, Catarina Carriço Marques de Moura Belo, Chance and determinism in Avicenna and Averroës, p. 228. Brill, 2007. ISBN 90-04-15587-2.

- ^ George Saliba, Avicenna: 'viii. Mathematics and Physical Sciences'. Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition, 2011, available at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/avicenna-viii

- ^ Livingston, John W. (1971). "Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah: A Fourteenth Century Defense against Astrological Divination and Alchemical Transmutation". Journal of the American Oriental Society 91 (1): 96–103. doi:10.2307/600445. JSTOR 600445.

- ^ Livingston, John W. (1971). "Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah: A Fourteenth Century Defense against Astrological Divination and Alchemical Transmutation". Journal of the American Oriental Society 91 (1): 96–103 [99]. doi:10.2307/600445. JSTOR 600445.

- ^ editor, Peter M.J. Stravinskas, (1998). Our Sunday visitor's Catholic encyclopedia (Rev. ed. ed.). Huntington, Ind.: Our Sunday Visitor Pub.. p. 111. ISBN 0879736690.

- ^ a b Hess, Peter M.J.; Allen, Paul L. (2007). Catholicism and science. (1. publ. ed.). Westport: Greenwood. p. 11. ISBN 9780313331909.

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church - Part 3". http://www.vatican.va/archive/ccc_css/archive/catechism/p3s2c1a1.htm. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

[edit] External links

| Find more about Astrology on Wikipedia's sister projects: | |

| Definitions and translations from Wiktionary | |

| Images and media from Commons | |

| Learning resources from Wikiversity | |

| News stories from Wikinews | |

| Quotations from Wikiquote | |

| Source texts from Wikisource | |

| Textbooks from Wikibooks | |

- Astrology at the Open Directory Project

- Digital International Astrology Library at C.U.R.A. (Centre Universitaire de Recherche en Astrologie) International Astrology Research Center; (Retrieved 15 November 2011).

| |||

| ||

| |||||||||||||||||

| ||

| ||

| ||

No comments:

Post a Comment